One place study - studies

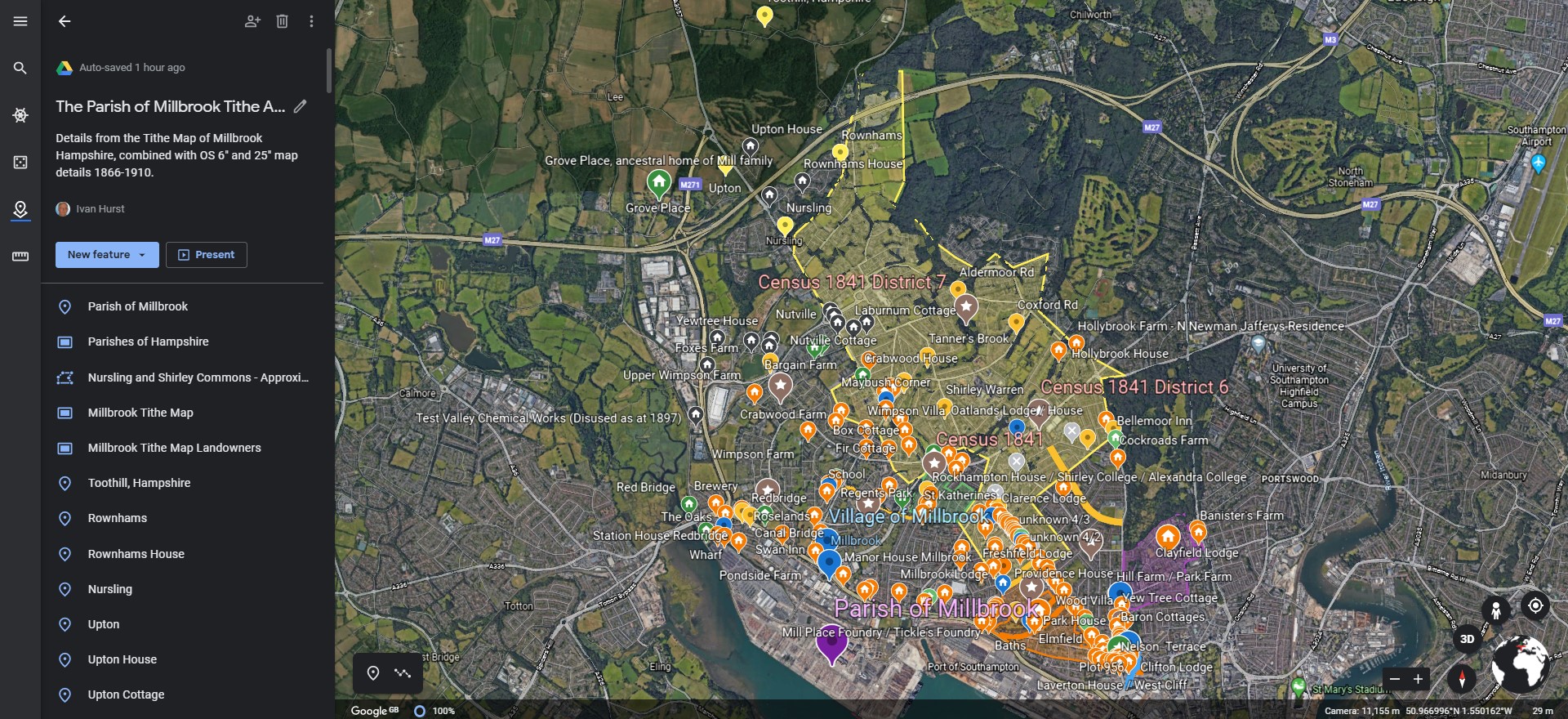

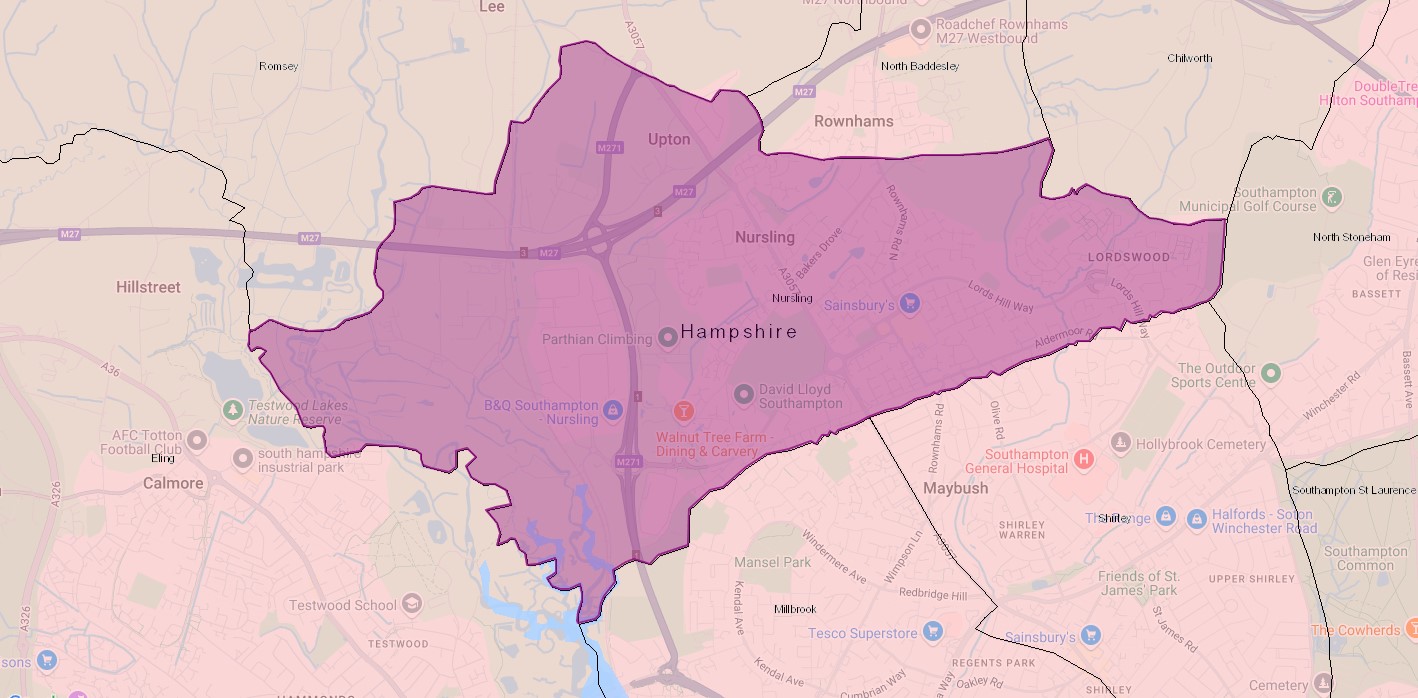

My interest in one place studies started with the 1841 census at Millbrook Hampshire. According to MyHeritage there are only 3496 records for 1841, which increased to 12,863 for the 1891 census. Millbrook, Redbridge, and Nursling were all adjacent rural communities with very low density populations. I have been following the enumerators described roues to try to establish residences and plot them on a map. Communities were fairly static in the early part of the census taking period before WWI. There had been the earlier mass migrations caused by the industrial and agricultural revolutions, exasperated by the enclosure laws. I am expecting to find some families stay in close proximity to the first census and have a tendency to marry the girl/boy next door. Well, near neighbours. By studying one census location from 1841 to 1911, I hope to be able to shed some light on he social change as the population again starts to migrate again and the area becomes urbanised and absorbed into Southampton.

However, before the first, Milbrook, was complete, others popped along, that needed a similar treatment.

This is a collation of them as they currently stand.

Millbrook Parish one place study

Nursling One Place Study

'One Place Study' of Whiteparish

Eling One Place Study

Millbrook Parish one place study

A Study of the Parish of Millbrook, Hampshire

My Millbrook Parish one place study The beginning was actually just a restart triggered by a post in the Facebook group of Guild of One-Name Studies by Karen Heenan-Davies on 7 August 2018.

'I want to do analysis and maps of the BMD and census records to show how my surname Heenan changed geographically over time'

Well that got me thinking about how I had started plotting the Enumerators route of the 1841 Census of Millbrook. It was very rural then.

Link that to thoughts of GIS and BIM, and I join the conversation.

Later that day I start a new Google Map of Millbrook and using the Census images on Ancestry I start plotting the routes and key named places. I also start a spreadsheet which will expand the data extracted from the Census and also provide the upload to ESRI for the interactive ARCGIS Mapping.

Overview

Obviously it is not that easy a task to locate things mentioned on an 1841 Census and plot them on a current Google Map. My process varies but the simple version is;-

- Can the place still be found on current mapping? If so use that data to plot on my map.

- Try to locate the place on a Ordnance Survey map of the period, either paper or those digitised maps held my the National Library of Scotland Mapping. There are other sources of OS maps, but this one is free to use.

- Compare the location of the found place with current maps, there is a slider to change the transparency of the old to new maps on the NLS georeferenced maps, as well as a 'Spy' button.

- Search the internet for additional data, either prime or as corroboration.

- I use Grid Reference Finder to translate any location data into Latitude Longitude and to check the satellite image to ensure correct positioning.

- I create layers on my map to correspond to the Census Enumerator Districts.

- I use the search by inputting the Lat Lon (cut and paste) to find the position and plot the pin onto the map in the appropriate layer.

All of this is just to get an understating of the Census walk or route, to help provide location information to each of the homes recorded on the Census.

But it is not even that easy as some names are not to be found. For instance Turnpikes turned into their own mini study with it's own article on this site.

The map below is the result of adding Turnpike data of the area to a current Google map, and any information found so far.

The map can be enlarged by the icon top right and a menu shows with the icon on the top left. Layers with information on Turnpike roads and tollhouses, as well as individual Census Districts can be turned on or off.

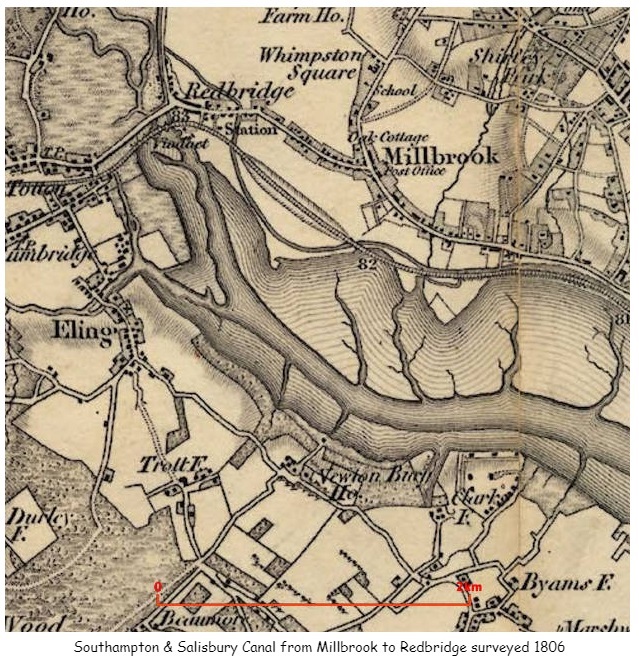

It is commonly accepted that places and maps change over time. This is further complicated by shorelines changing, mudflats becoming docks and canals becoming railway lines or backfilled. District one has all of these problems. An old 1871 OS map shows all of the old positions. Some of these are approximately replicated on the My Maps.

The canal in question is of the Southampton and Salisbury Canal Company and there are photos of the locations together with the plan, old, and current maps. There is also a map of the area in the British Library.

The above map not only shows the canal but also other places around Millbrook including Whimpston Square, which correlates with Wimpston on later maps and a road called Wimpson Square on a 1911 Census record for a family called Street.

The link to the British Library held maps provided invaluable additional information including additional information about names and locations of Turnpike gates to confirm or correct data sourced elsewhere.

A named boundary of the 1841 Census is Cockerwood Land, in District 6 for instance. However, I have not found that road on any current map. There is some reference to Hill Lane on a paper about Taunton's College and a Cockroads Farm shown on some of the old OS Six inch maps.

'A map of Southampton in 1800, by Doswell shows a building next to Hill Lane and known as Cockerwood House. The first OS map of Hampshire shows an unnamed building within a rectangular enclosure. The details are very similar to those shown on the 1826 map of Hampshire. The enclosure map of Hill and Shirley in 1830 shows two main building complexes, both aligned north–south, one adjacent to Hill Lane and the other, to the north-west of it, set slightly back from Hill Lane. This second building interrupts a rectangular enclosure that otherwise surrounds the building on Hill Lane.'

OS 1866 Map Link There is also a short article on Sotonopedia There is also relevant information on OS First Series Map showing Whithedswood Common. Even more interesting is the British Library held map. This map appears to predate the OS First Series and includes Shirley Common, Warren, Shirley, Hill, Whiterswood Common, Cock Road, Shirley House, as well as Millbrook and Redbridge. Whilst the map does have the words Shirley House it is not clear exactly where it is. Possibly somewhere close to Foundry Road. Later maps pin point Shirley House, which in turn suggests that what appears to be Shirley Brick, on the 1806 map above is in fact Shirley Park.

Unsurprisingly, research into one area takes you to another. The Parish of Millbrook on British History Online leads to manors of Millbrook, which again leads to the Manor of Shirley, and latterly Shirley and Hill. This article provides some of the names of the Lords of the Manor in the 13th and 14th Centuries. I will add these names to my One Place Ancestry Tree, The people of Millbrook. Sometimes the entries produce hints and additional information about the person and their family. The most successful of these so far was the Whitehead family who held the the Manor of Shirley and Hill from 1433 until Mary, the daughter of Henry and Mary, married Alexander Thistlethwayte in 1717, and the manor thus passed to the Thistlethwaytes with whom it remained for a further considerable period. Whilst they were holders of the Manor of Shirley and Hill, their main seat appears to have been in Norman Court, West West Tytherley, Hampshire, on the border with Wiltshire. Indeed, Norman Court Park is shown on the OS Map as being the boundary between Hampshire and Wiltshire. Norman Court Park is about 20 miles away from Shirley, so I am unsure if they ever lived in Shirley House. Further investigation quickly reveals that Shirley House was built in the later part of the 18th century for retired West Indian plantation owner, Richard Wilson. It stood at the junction of modern-day Clarendon and Henty Roads. The site is bisected by modern Shirley Park Road, which was named after the estate. Sales particulars of 1792 show it to be a substantial dwelling, with double coach houses, stabling for eight horses, pleasure gardens, a small farm and a large paddock, the total comprising about 48 acres. In 1802 it was occupied by the Reverend Sir Charles Rich and it remained with that family until 1836, when it was sold to property developer William Henry Roe. Roe eventually sold off the estate for development and the house was demolished in the 1880s. More names to add to the Ancestry Tree.

Information on Manors can also be found at the National Archives. The search for Millbrook manor reveals 34 collections held in 4 archives with a date range of 1189 to 1925. Some of these also refer to Nursling Manor, perhaps as the main manor of the two, with some records held at Winchester. Hampshire County Council in the form of the Hampshire Records Office also has a significant number of records, including for instance;-

Plan of Hill and Shirley manor (Whitheds Wood), Millbrook, property of Robert Thistlethwayte, 1778; plan of Hill and Shirley enclosure, 1830; mortgage of tenement on south side of Winchester, John Osman to Elizabeth Merriweather, 1694.

If Nursling Manor and Millbrook Manor are so linked in court records, should I expand my One Place to be Nursling and Millbrook?

Whilst some of the previous holders of the Manor of Shirley have also been Mayor of the adjacent town, the list of Mayors of Southampton does not include a Whitehead.

The Ancestry tree now includes many generations of Whitehead due to this. Also, I have created an article about Shirley on this site.

Off I go on another side road. From Shirley House or Park, the trail leads me to THE COUNTRY HOUSES OF SOUTHAMPTON By JESSICA VALE. Another paper by the Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society. However, perhaps this is not quite so much of a diversion. Some of the early Census Enumerators record the route taken by reference to the large houses of the time, whilst others just record something like 'Shirley Common' for almost the whole of the census. The latter not entirely helpful in establishing locations of dwellings. Even so, sometimes historical papers of old houses reveal the names of the occupants which can be correlated to the census.

The occupancy of Shirley House by the Rich family led me to another long line in Ancestry, then confirmed by other sources.

The Rich Baronetcy, of Shirley House in the County of Southampton, was created in the Baronetage of Great Britain on 28 July 1791 for Reverend Charles Rich. He was the son-in-law of the fifth Baronet of the 1676, and had inherited the estates and assumed the name and arms of Rich. This creation became dormant upon the death of the sixth Baronet in 1983, but heirs are still thought to be living. From Rich baronets.

Another source was the Dictionary of National Biography, Volumes 1-22.

The Rich Baronetcy, of London, was created in the Baronetage of England on 24 January 1676 for Charles Rich, of Mulberton, Norfolk, with remainder to his son-in-law and distant cousin Robert Rich, son of Nathaniel Rich, who inherited the baronetcy the following year. He was a successful politician. His younger son, the fourth Baronet, was a distinguished cavalry officer. The title became extinct on the death of the sixth Baronet in 1799.

Looking into a Nathaniel Rich 1585-1701 takes us into the English Civil War and the formation of the New Model Army. Nathaniel became Colonel of a regiment of horse upon the formation of the New Model Army and was therefore among the first of our professional Army. He fought on Cromwell's side against the King.

I wonder, is the fact that the formation of the current professional army traces back to the Parliamentarians, the reason why it is not a Royal Army, it the way that Royal Navy and Royal Air Force are.

I have just found a possible source of tithe maps of the parishes of Hampshire. This has the potential to significantly aid the correlation of places and families in the 1841 census.

Two interesting metrics I am trying to include into my spreadsheet are voting and adulthood status which requires date thresholds. An interesting summary of the English path to democracy is on the National Archives site.

In my meanderings around the Fifield family and the Standbridge Estate, I found the name Humby, and I have a later relative William Edward Humby 1831-1906; father-in-law of 2nd great-aunt who lived in 1 Rose Hill Cottages, Romsey Road, Old Shirley, Millbrook, Hampshire, England. I have found him in the 1871 Census which I have plotted the Enumerators route and William's home on the map below.

One of the interesting and challenging aspects of plotting locations found in Census returns is the passage of time has eradicated a large number of the buildings and places mentioned. Therefore they cannot be directly plotted onto a current map. Even some current roads were previously known by another name. Reference to old maps helps to resolve some of the locations. It is a slow process, but a worthwhile investment in time and effort. The map below is a collection of places found and plotted. It is still growing, and becomes the basis of Census Enumeration route plots, which in turn will feed data into an ESRI data map.

Another interesting, albeit sometimes unlikely, source of information, is Facebook. There is a group called Freemantle Local History Group. It is fascinating. It is a private group so although I have included links to information sources they may not open for you.

Cedar Lodge House, off Oakley Road, was built in the mid nineteenth century. It was originally called Mussoorie Villa (after a place in northern India). Nearby 2.68 acre Cedar Lodge Park named after the house opened in 1967. Oakley Road was originally called Mousehole lane, renamed Oakley Road in 1909 in honour of the then Mayor, Richard Garrett Oakley.

Another link in the group led me to a collection of Old Maps of Hampshire.

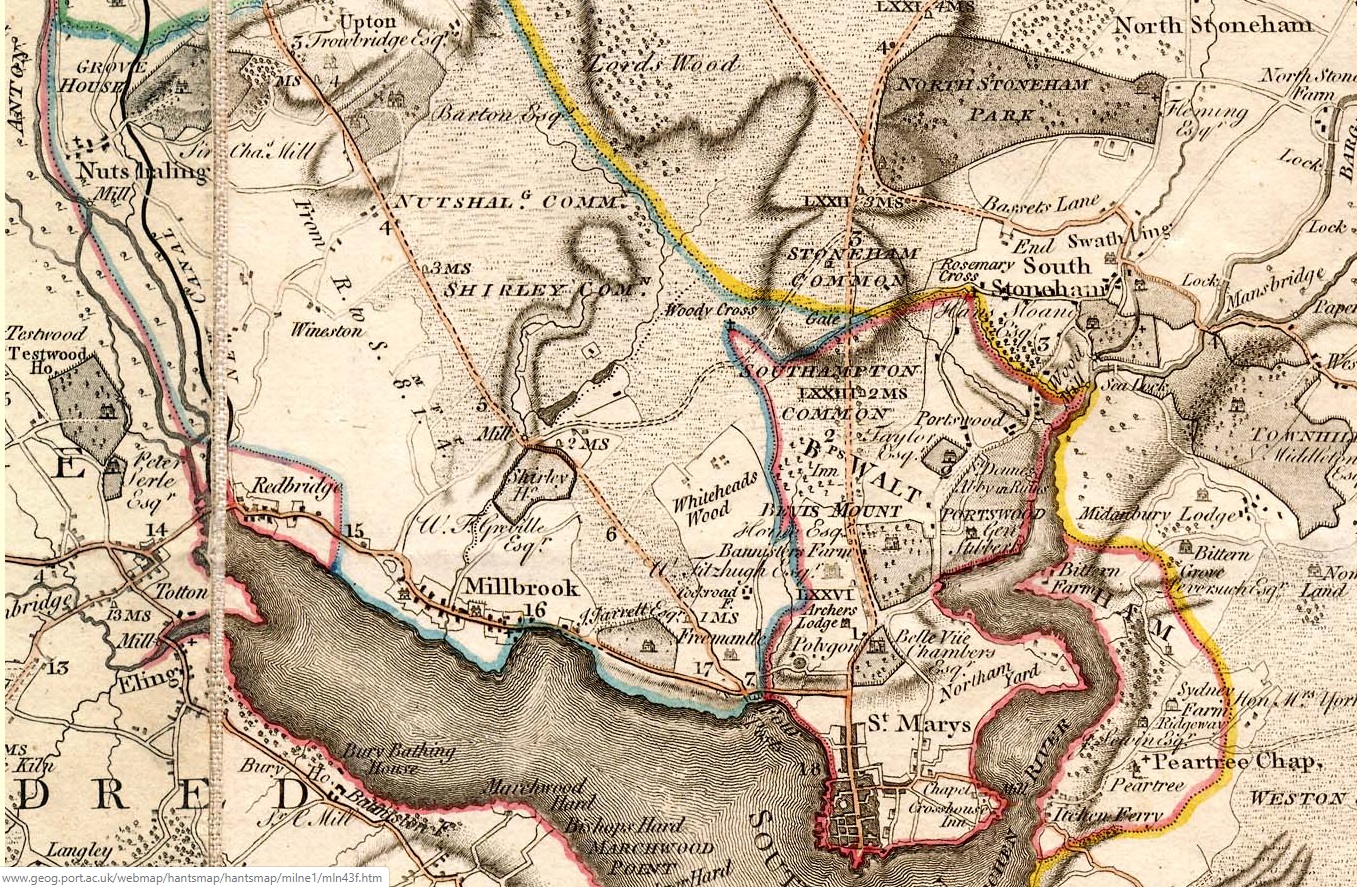

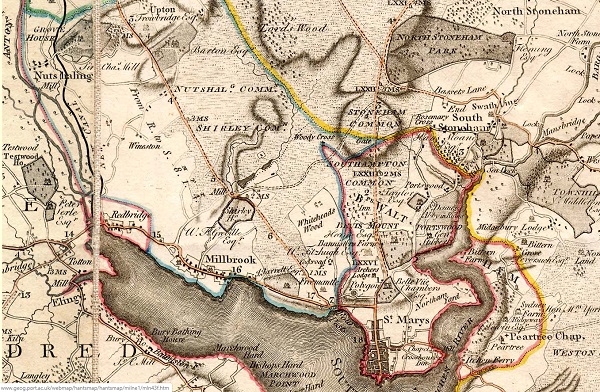

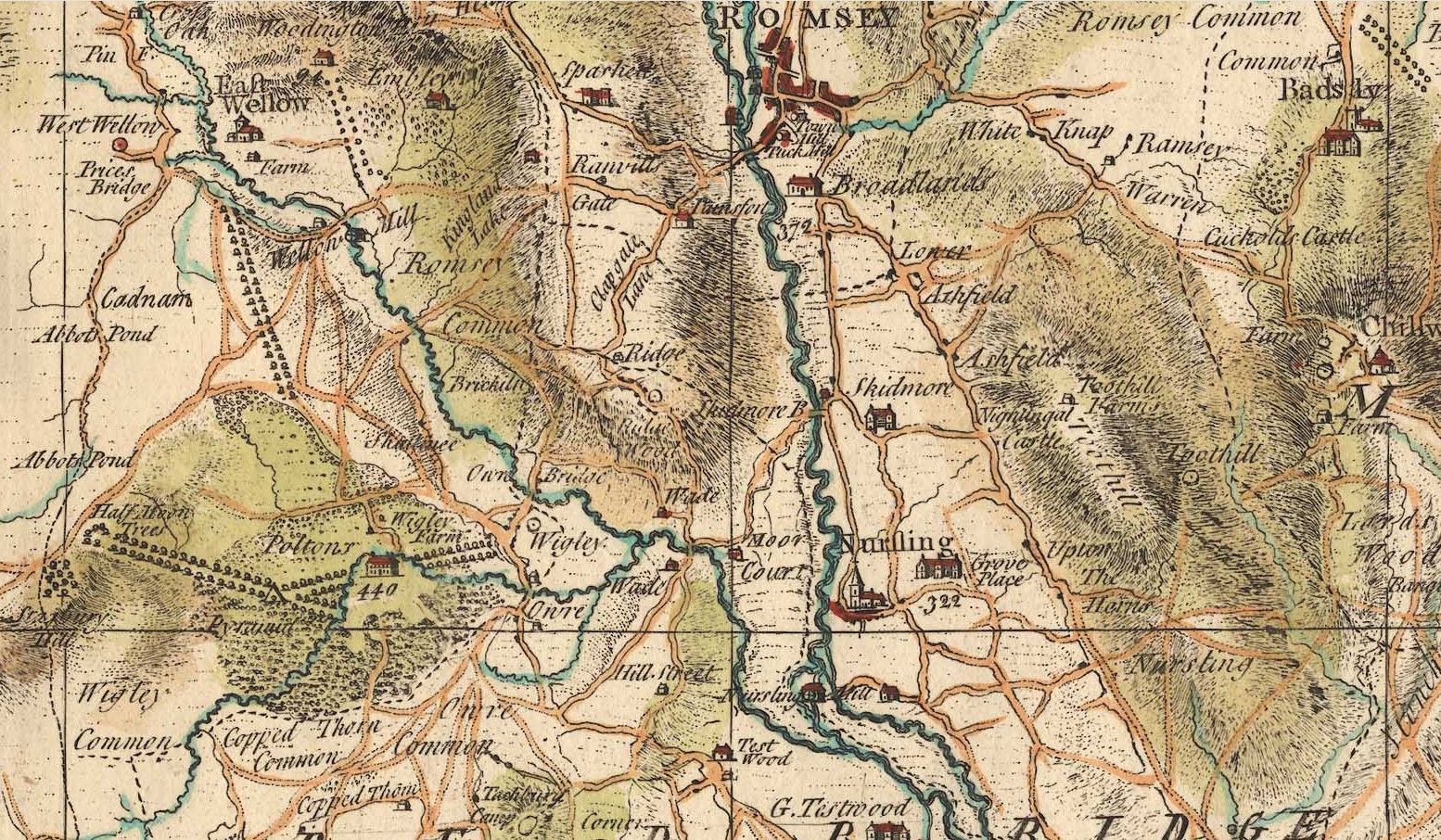

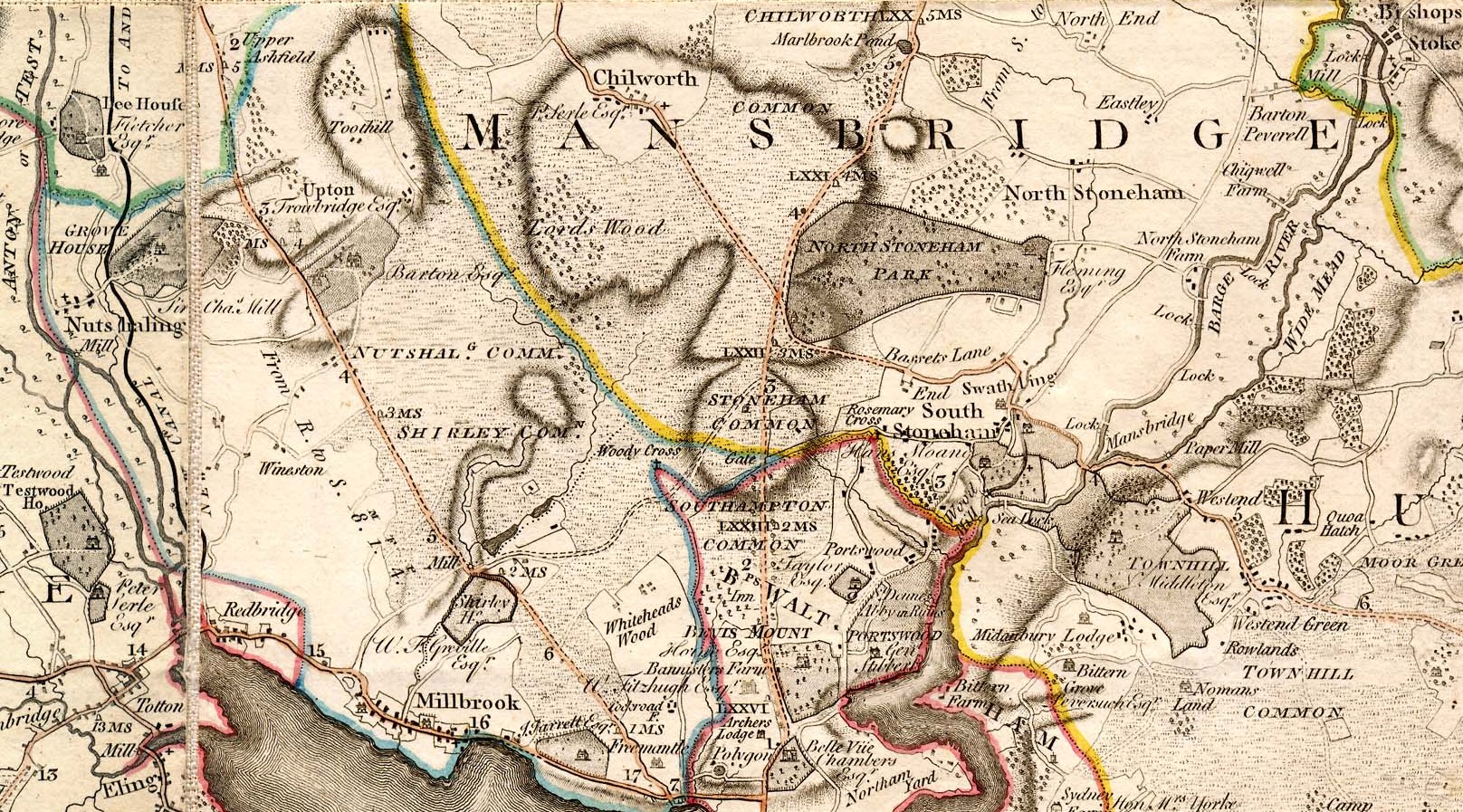

Milne's Hampshire 1791 section 43

The map shows how rural the whole area was in 1791, with the majority either estates or a huge area of common land. The estates appear to have the names of the owners associated with them. J Jarrett Esq was annotated above Freemantle Park. The size of Nutshalling Common, Shirley Common, and Whiteheads Wood is amazing. So much land in Common usage. Just a few years later the impact of the agricultural and industrial revolutions were clear to see. On the one hand, it is a major land grab by the establishment and the wealthy, but on another it is increasing the productivity of the underutilised and uncared for land, to feed an expanding population. Name changes are also an important consideration. Nutshalling has previously been Nhutscelle, Hnutscilling, Nutshullyng and is now known as Nursling. Whiteheads Wood on this map becomes variously Whitheds Wood, Whithed Wood on later maps. Whithedswood Road becomes Shirley Avenue. Wynsor is shown on this map as Wineston and is now Wimpson. Old roads such as Romsey Road are clearly shown and are still evident whilst Millbrook Road, whilst on a similar alignment but considerable developed. Turnpikes have also come and gone. Shirley is recorded as a manor with a mill in the Domesday Book; the mill standing to the west of the present Romsey Road/Winchester Road junction, at the confluence of the Hollybrook and Tanner's Brook streams. Shirley Mill had three large ponds, to the north of Winchester Road. One of the three mill ponds remains today, accessed by following the Lordswood Greenway. The mill can be seen adjacent to Shirley House and both Hollybrook and Tanner's Brook streams can be seen meandering towards the mill through Nutshalling and Shirley Commons.

Another Map, Taylor's Hampshire 1759 section 43

Millbrook is clearly shown on this map, with Freemantle, Vaux Hall, and Four Posts between it and Southampton. Mouse over the image to zoom in to Millbrook. Grove Place and Nursling is at the top the map. Shirley, despite being mentioned in the Domesday Book is not identified on this map.

Shirley was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Mansbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 12 households in 1086.

Land of Ralph of Mortimer

Households

Households: 4 villagers. 3 smallholders. 5 slaves.

Land and resources

Ploughland: 8 ploughlands. 2 men's plough teams.

Other resources: Meadow 12 acres. Woodland 6 swine render. 1 mill, value 2 shillings and 5 pence. 1 fishery. 1 church.

Valuation

Annual value to lord: 5 pounds in 1086; 5 pounds when acquired by the 1086 owner; 5 pounds in 1066.

Owners

Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Ralph of Mortimer.

Lord in 1086: Ralph of Mortimer.

Overlord in 1066: King Edward.

Lord in 1066: Cypping (of Worthy).

The Domesday Book records a church being present at Shirley in 1085, but on 1 May 1574 the parish of Shirley was amalgamated with that of Millbrook as the small Shirley congregation could not afford the upkeep of the Shirley church building. The Shirley church was demolished in 1609, with stones from the old building used to enlarge St Nicholas' Church building in Millbrook.

By 1836, the population of the combined parish had reached 2,375 inhabitants, and the old Millbrook parish church was too small. Land was donated for a new church building in Shirley by Nathaniel Newman Jefferys, and Church Building Society combined with private funding to pay for the structure itself. The new church, dedicated to St. James, was designed by local architect William Hinves and consecrated on 20 August 1836 by the Bishop of Winchester with a large crowd present despite "unfavourable weather", according to the Hampshire Advertiser newspaper.

Some extracts from a paper presented to Hants Field Club entitled FIELD SYSTEMS AND ENCLOSURES IN HAMPSHIRE

Hampshire was among the counties reported upon by Wolsey's Commission in 1517.

... 37 Hundreds and eight liberties at which the County (including the Isle of Wight) was divided. The Hundreds for which enclosures are recorded are :

Basingstoke, Crondall, Kingsclere, Mansbridge, Odiham, Redbridge, Shutterley (i.e. • Chuteley) and Somborne, and the places. mentioned are : Al( d)ington recte Aldington, Bewraper (Beaurepaire), Bramsyll " Breche and Sockborowe " (field names only ?),. Dogmersfelde (Dogmersfield), Erleston (Earlston), Ewurst. (Ewehurst), Farley . (Fafleigh Chamberlayne),- Ichill, " Loke Dewer," " Newtosberye," Wynsor (in Millbrook Parish ?), and the total area is some 562 acres.

Hampshire is not included among the 14 counties covered by the Depopulation Act of 1536, though curiously enough the Isle of Wight is.

The County Agricultural Survey was written by the. Drivers, who describe themselves as " of Kent Road, Surrey." They are sorry to observe in the County such immense tracts of open heath and uncultivated land, which tend to remind the travellers of voyages among the barbarians ; they point out, however, that in this respect Hampshire is no worse than Wiltshire and Dorset, perhaps a trifle better. This is no excuse for it. Near Southampton is a great deal of open land which if enclosed and cultivated will give good crops of corn. There are large downs towards Fareham and Warnford,85 and much open land with some good down near Petersfield. As to the forests and wastes, the Drivers are astonished that the Crown Lands in particular should have remained so long in a state of neglect. If properly managed they would pay much of the interest on the National Debt. A general Act should be passed at once, preferably entrusting enclosure to the Commissioners of Crown Lands:

As to other open land, it might well not be worth enclosure for tillage, and still be worth taking in for planting. No " gentleman can sit down easy, and say he has discharged his duty to his family when he is conscious he has neglected to pursue those measures, which, in a few years, would increase his property so amazingly." . Commonable land of every kind can be regarded as little better than waste, since everyone exhausts it, and no one pays the least • attention to. its support and improvement. "All this would be easily remedied by a general inclosure bill, which would reduce the expense. of inclosures, and would be a spur to that improvement." Wool production would certainly not decrease on enclosure, every farmer in his own interest keeps as many sheep as he is able, and he can feed twice as many on land in severalty as on the corresponding area in common.

Note the reference to Depopulation and read more about it here. By 1530 the population of England and Wales had risen to around 3 million. At the end of the 17th century it was estimated the population of England and Wales was about 5 1/2 million. The population of Scotland was about 1 million. The population of London was about 600,000. London went on to become the biggest city in the world for a while. In the 19th century Britain became the world's first industrial society. It also became the first urban society. By 1851 more than half the population lived in towns. As our population approaches 70m it is interesting to think of depopulation efforts at 3 million! The maps of Millbrook clearly show the urbanisation of the countryside.

Following the Tithe Commutation Act 1836 Tithe Maps were produced which recorded both the Landowner and Occupier for most lands. From the Tithe Apportionments records it is apparent that on 4th March 1843 Lady Hewitt

was both the Landowner and Occupier of Plot 875, Freemantle Estate, described as House Offices and Pleasure Grounds, with an area in statute measure 6,0,2, about 2.4 Hectares.

Nathaniel Newman Jefferys was both Landowner and Occupier of Plot 825 described as House Offices and Garden, an area of 2,2,24 imperial, on 4th March 1843. However, one plot does not show the full picture.

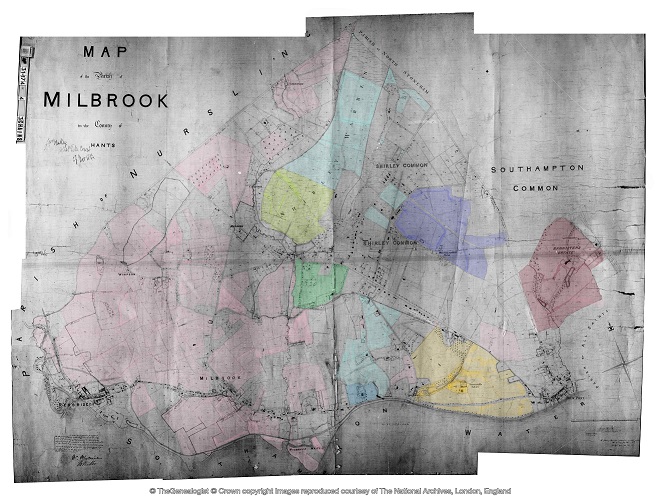

Using the Tithe Apportionment map of the Parish of Millbrook, Hampshire, as a base, I have colour washed some of the plot landowners. The Freemantle and Banister Estates, pale orange and brown respectively can be clearly seen. The landowners in 1843 where Lady Hewitt and Reverend William Fitzhugh. Shirley Park, owned by William Henry Roe, is in green. Blightmont Lodge, occupied by Lady Lisle, just north of Millbrook Road, and part of the larger Berrywood estate owned by Nathaniel Newman Jefferys is shown in a slightly darker blue than the light blue of the rest of the estate. It appears that Nathaniel Newman Jefferys has bought a large swath of the newly released Shirley Common land in the area of Shirley Warren. Clement Hoare & William Dunn seem to have also taken advantage of the inclosue of Shirley and Nutshalling Commons, as joint owners of plots coloured lime green. Roads such as Warren Avenue, Warren Crescent and Tremona Road have already been laid out for the impending urbanisation. However, the biggest landholding in the Parish, by a long way, is Sir John Barker Mill and various associates who together are landowners of the pink coloured plots, mainly farmland in 1843, but destined to be developed and absorbed as suburbs of Southampton.

Greenwood's Hampshire 1826 section 53

Moving into the current, the Church of England has a database of interesting statistics about all the Parishes in the country. Below is the Map which covers the original Millbrook Parish and shows the current Parishes of;

Millbrook: Holy Trinity

Freemantle: Christ Church (1851)

Shirley: St James (1836)

Maybush.

Click on the parish to bring up the statistics.

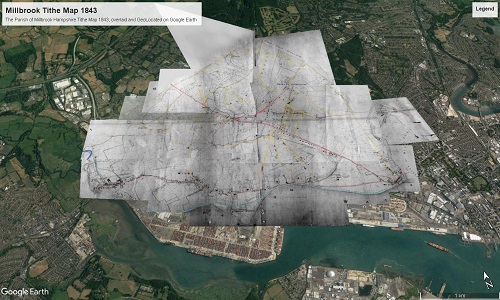

The Parish of Millbrook Tithe Map 1843 including Shirley, Freemantle and Four Posts, layered onto Google Earth Pro and Geolocated. Same base map as the coloured ownership map. Over 20 separate tiles or files to fit spherical base globe of Google Earth. All adjusted to best fit the projection, and align roads and as many details as possible. Below is just an image of the result. Google Earth Pro is desktop based so does not lend itself to sharing. However, using transparency of the layers I can locate buildings on the tithe map and see what is there now. I can also use the Lat and Lon and show on Google Maps to georeferenced individual buildings or plots.

The interactive version is created using a Project in Google Earth and can be seen here, The Parish of Millbrook Tithe Apportionment. Using the Tithe Map plotted on Google Earth Pro above and other maps, I have placed some of the Property names onto a Google Earth Project with an up to date backdrop. History mapped to now.

A screenshot as at March 2020. Work ongoing.

Freemantle

Freemantle Estate

Before 1600

1600 to 1800

Tithe Apportionment and Map

Tithe Apportionment and Map

Census

Your text...

1939 Register

Your text...

Post 1939

Your text...

People

People

People of note in the parish of Nursling, through time.

Your text...

Relatives

Relatives

Some of my relatives with an association to the parish of Nursling.

Your text...

Spare

Your text...

more later

'One Place Study' of Whiteparish

Whiteparish is a small village in Wiltshire, England, in the Parish of Whiteparish

There is a possibility that some of my ancestors lived there and migrated from there.

This is the investigations of that one place, the Parish of Whiteparish.

For an overview of the history of the village of Whiteparish see this community page.

Before 1600

...

Between 1600 and 1800

...

Tithe Apportionment 1840

Tithe Apportionment - Parish of Whiteparish, Wiltshire

There is a possibility that some of my ancestors lived there and migrated from there.

That requires further investigations.

This is part of those investigations. There are three main streams, one is via ESRI ArcGIS StoryMap and another other a spreadsheet based database. The third is the normal family tree, both in Ancestry and TNG. The TNG list of the people of Whiteparish currently starts with Elizabeth born in 1565.

A child with the surname Hurst was born in 1564, and Edith Hurst was born in 1566, both in Whiteparish. The question of are these people related remains un-answered at the moment.

Intorduction and Conclusion

Story Map and Graphical Display of data

The StoryMap is below, and the spreadsheet full of interesting records below that. The Story Map Tithe Apportionment Parish of Whiteparish can also be open in a new window by clicking on the link.

Depending on your computer and your internet connection you may have to be a little patient and allow the StoryMap time to load the maps and images.

Notes

Transcription

Dataset

The Dataset

The dataset comprises all of the transcribed information from the Tithe Apportionment and Maps together with additional information, including, inter alia, geolocation and census data. All held in an Excel Spreadsheet. The data is both analysed within the spreadsheet and formed into reports for export as csv files to populate the StoryMap data.

Primary Data

Primary Data

The primary data for this parish Tithe Apportionment pulled together as a simple reference document

Detailed Data - Summary

Detailed Data - Summary

Pending population

Detailed Data - Landowner and Occupier Summary

Detailed Data - Landowner and Occupier Summary

Pending population

Detailed Data - Schedule

Detailed Data - Schedule

Pending population

Spare

Pending population

Land Usage

Graph of Land Usage in Whiteparish in 1842 from the Tithe Apportionment information.

Analysis of the land usage based on the Tithe Apportionment information, showing the primary use as arable at 61%, and secondary usages of woodland 18% and pasture 16%. Common and Furze land has been reduced to about 1%, presumably as a result of the Inclosure Acts, (Enclosure).

Land Ownership

Graph of Land Ownership in Whiteparish in 1842 from the Tithe Apportionment information.

Land Ownership is more widely distributed than in some parishes that I have looked at.

Scroll right to see the list of landowners associated to the graph.

Plot register

The Table with all the data of the Detailed Plot register.

This table has the Landowners and Occupiers of all the Plots in the Parish, including the Description or Names of the plots together with the State of Cultivation. It instances where there is no entry, but it is evident what the Land Usage is I have added the category surrounded with { Brace Brackets }. Not relative to the Tithe Apportionment as some of the Land Usage is not part of the charge regime, however {Residence), {Premises} and {Retail} etc are useful additions. There are approximately 220 Mansions, Houses, or Cottages etc, across the Parish.

The areas of each plot together with the Rentcharge amount in respect of both the Small and Great Tithe, for the Vicar and Impropriator.

Top Ten Landowners

Top Ten Landowners in Whiteparish from the Tithe Apportionment information

From this analysis of the plot level detail for the Parish of Whiteparish the Top Ten Landowners own 91% of the whole recorded area of the parish. Two of the Landowners were relations to the Nelson of The Battle of Trafalgar fame.

Horatio Nelson, 3rd Earl Nelson, (7 August 1823 – 25 February 1913), was 16 years 9 months 7 days at the recorded data of the survey, 14th May 1840, a Minor, hence the Guardians of ...

He was the son of Thomas Bolton (a nephew of Vice Admiral The 1st Viscount Nelson) by his wife Frances Elizabeth Eyre. On 28 February 1835 his father inherited the title Earl Nelson from William Nelson, 1st Earl Nelson and adopted the surname of Nelson. He died on 1 November that year, and his son Horatio succeeded to the title and the estate, Trafalgar House in Wiltshire, in the nearby parish of Downton. The Eyre Family were the owners of Brickworth Park according to the Turnpike Acts for the Whiteparish Romsey Southampton Road. The Dowager Countess Frances Elizabeth Nelson was recorded as being the Landowner as Brickworth Park.

The remainder are either titled or referred to as Esquire. Although not all of the Esquires are in the top ten.

more later

...

Census

...

1939 Register

...

Post 1939

.

People

People

People of note in the parish of Whiteparish, through time.

Your text...

Relatives

Relatives

Some of my relatives with an association to the parish of Whiteparish.

Your text...

...

Spare

...

more later

Nursling One Place Study

Nursling One Place Study

A Study of the Parish of Nursling in the County of Hampshire, or sometime known as the County of Southamptonshire.

I refer you to the Millbrook One Place Study in the first instance. That has a lot of the background information which would be repetitive if just repeated here.

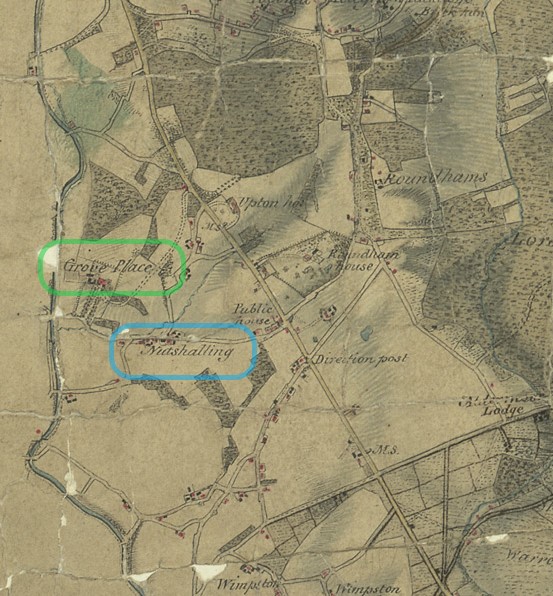

Nursling has also been called Nutshalling as can be seen in the Ordnance Survey drawing held at the British Library. Nutshalling is circled in blue. The nearby Grove Place is circled in green, the seat of Sir Charles Mills. Shirley, in the adjacent parish of Millbrook is circled in orange.

Overview

Overview

The Parish of Nursling

A Study of the Parish of Nursling in the County of Hampshire, or sometime known as the County of Southamptonshire.

I refer you to the Millbrook One Place Study in the first instance. That has a lot of the background information which would be repetitive if just repeated here.

For an extensive description of the parish follow the link to British History Online.

Nursling has also been called Nutshalling as can be seen in the Ordnance Survey drawing held at the British Library. Nutshalling is circled in blue. The nearby Grove Place is circled in green, the seat of Sir Charles Mills. Shirley, in the adjacent parish of Millbrook is circled in orange.

Before delving deeper, some information about the Ordnance Survey drawing held at the British Library. The British Library has also made the drawing available on Wikimedia The surveyor was: Crocker, Edmund - Medium: Pen and ink on paper - Date: 1806.

British Library notes;

This drawing was completed in 1806. The detail with which it records the road network is greater than in previous maps - testimony to the Ordnance Survey's urgency and military intent. The Roman road from Winchester to Old Sarum is marked running from the top left of the map, with smaller sections of the road shown in the Chilworth area. The origin and terminus of these roads are also noted. A line with a circle at each end leads from the margins of the map to Morstead. This line was used to plot locations and landmarks. Several "Ancient Entrenchments" are marked, notably an iron-age hillfort near Winchester called St. Catherine's Hill. The fort is indicated by concentric rings of dark, cross-hatched strokes ('hachures'). Week Turnpike Gate is marked on the road between Week and Winchester.

The recording of a dog kennel above Little Sombourne and bathing houses on the coast between Southampton and Redbridge reveal the meticulousness of the Survey, and perhaps too the interests of the draughtsman.

The map below is an extract of the map referred to in the British Library notes.

Not circled, but the following can also be seen on this map extract. Lordswood, Roundhams {Rownhams}, and Toothill, with the Telegraph. Together with a few named houses, Springford Cottage, Aldermore Lodge, Roundham House, Upton House, and Chilworth House,

This is the same Drawing referred to above but zooming to Grove Place and Nutshalling.

We are getting ahead of ourselves. Below we jump further back in time, to maps between 1575 and 1788. Nursling, or a variation of spelling of same, is shown on all the maps, despite how very small the village was.

|

|

| Saxton 1575 | Norden 1595 |

|

|

| Norden 1607 | Speed 1611 |

|

|

| Morden 1695 | Kitchen 1751 |

|

|

| Harrison 1788 | |

| The names and dates refer to the originator of the map and date. | |

| Click the link to go to the Old Hampshire Mapped website for more information. | |

| See how much the skill of mapping has changed over time. | |

We also need to look at some old large scale maps, also from the Old Hampshire Mapped website.

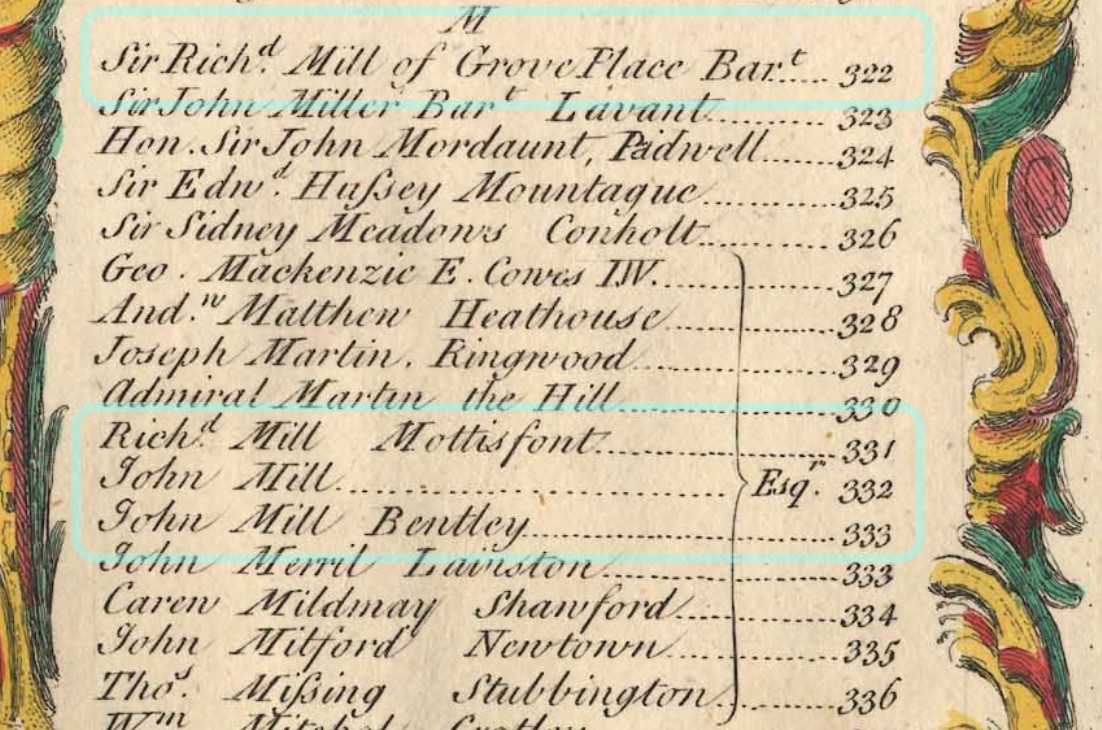

An extract of Taylor's Hampshire 1759. At 1759 this is not dissimilar to the period of interest of the article about John and Mary Mabey of Nursling. Grove Place is annotated 322.

The Mill family were prominent in the area for a long time.

An extract from Milne's Hampshire 1791. This map has names of prominent people added as well as places

| Named people on Map | Residence | Link |

|---|---|---|

| J Jarrett Esq | Freemantle House | http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:freemantle-house |

| W. F. Grenville Esq | Shirley House | http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:shirley-house |

| Sir Charles Mill | Grove House / Place | http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:grove-place |

| Peter Serle Esq | Testwood House | http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:testwood-house |

| Barton Esq | Rownhams House | http://sotonopedia.wikidot.com/page-browse:rownhams-and-rownhams-house |

| Trowbridge Esq | Upton House | https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/hants/vol3/pp433-439 |

| Fletcher Esq | Lee House | http://research.hgt.org.uk/item/lee-house/ |

Nutshalling / Nursling Common and Shirley Common is shown on this map. On later maps Shirley Common is much smaller, and in the area of Whiteheads Wood.

An extract of Greenwood's Hampshire 1826 with Nutshalling and Grove Place clearly shown.

The Parish

The maps so far show the village of Nursling or Nutshalling but not the extent of the parish.

NURSLING, or Nutshalling, a parish, in the union of Romsey, hundred of Buddlesgate, Romsey and S. divisions of the county of Southampton, 5 miles (N. W.) from Southampton. There is a place of worship for Wesleyans.

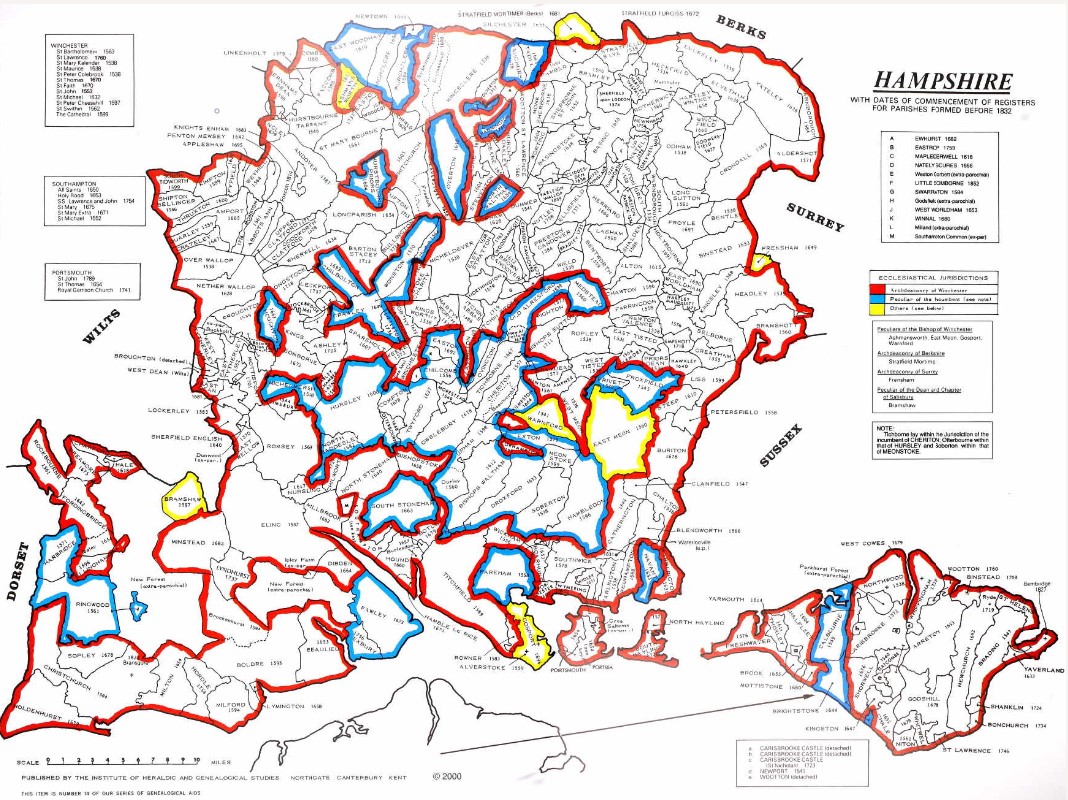

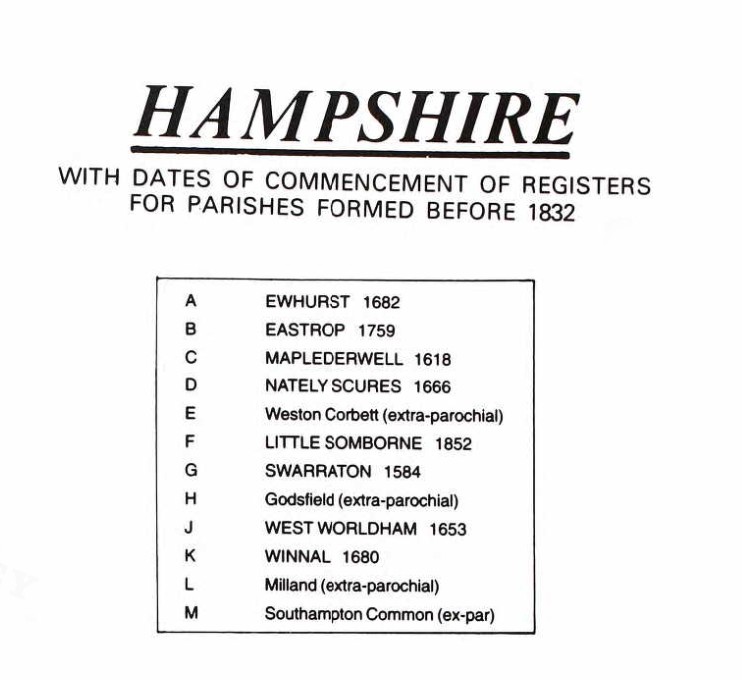

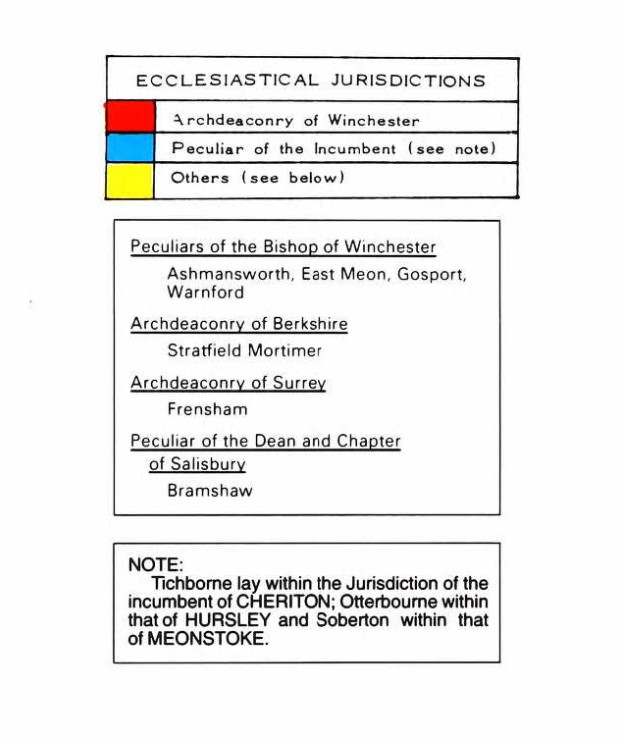

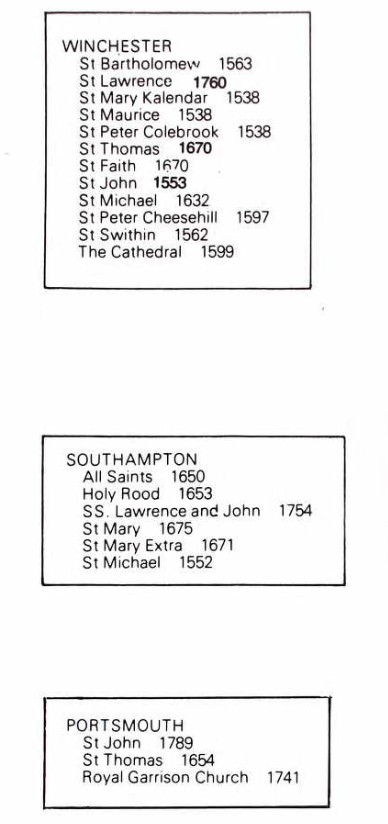

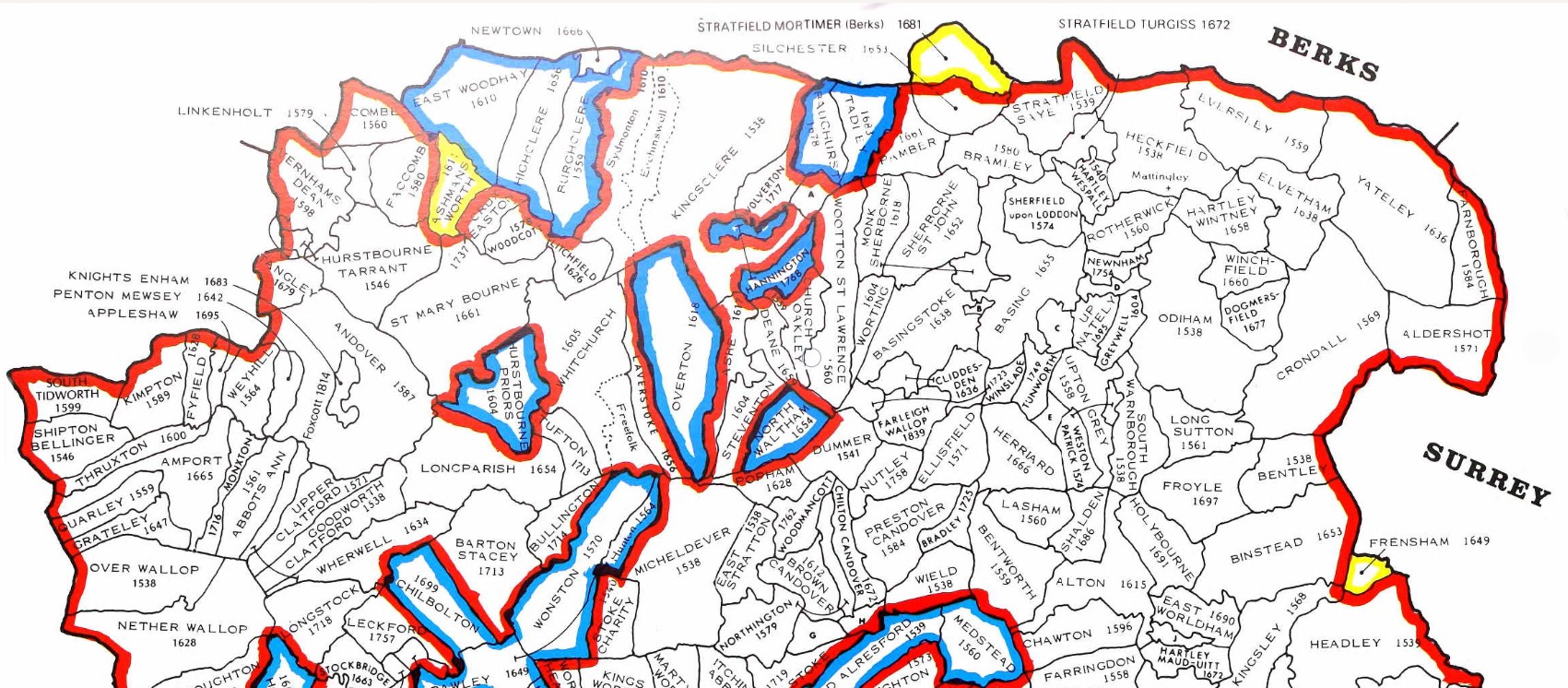

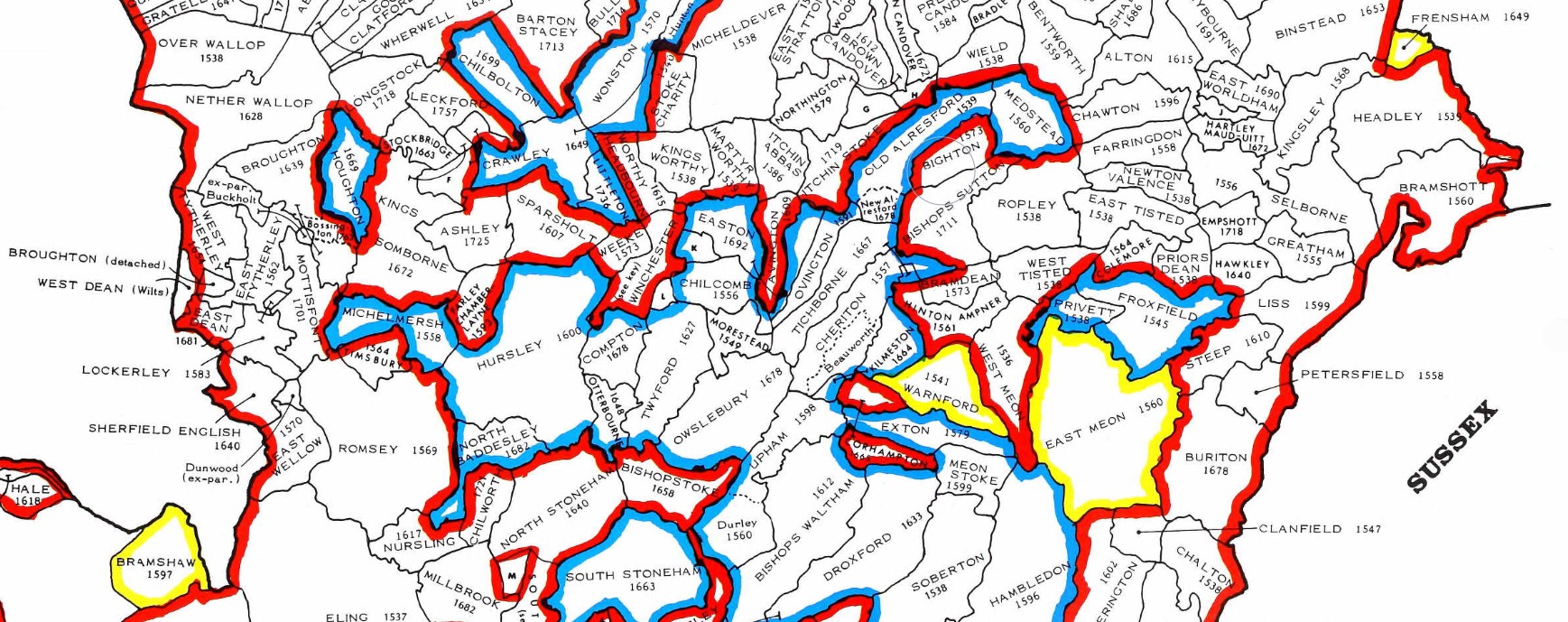

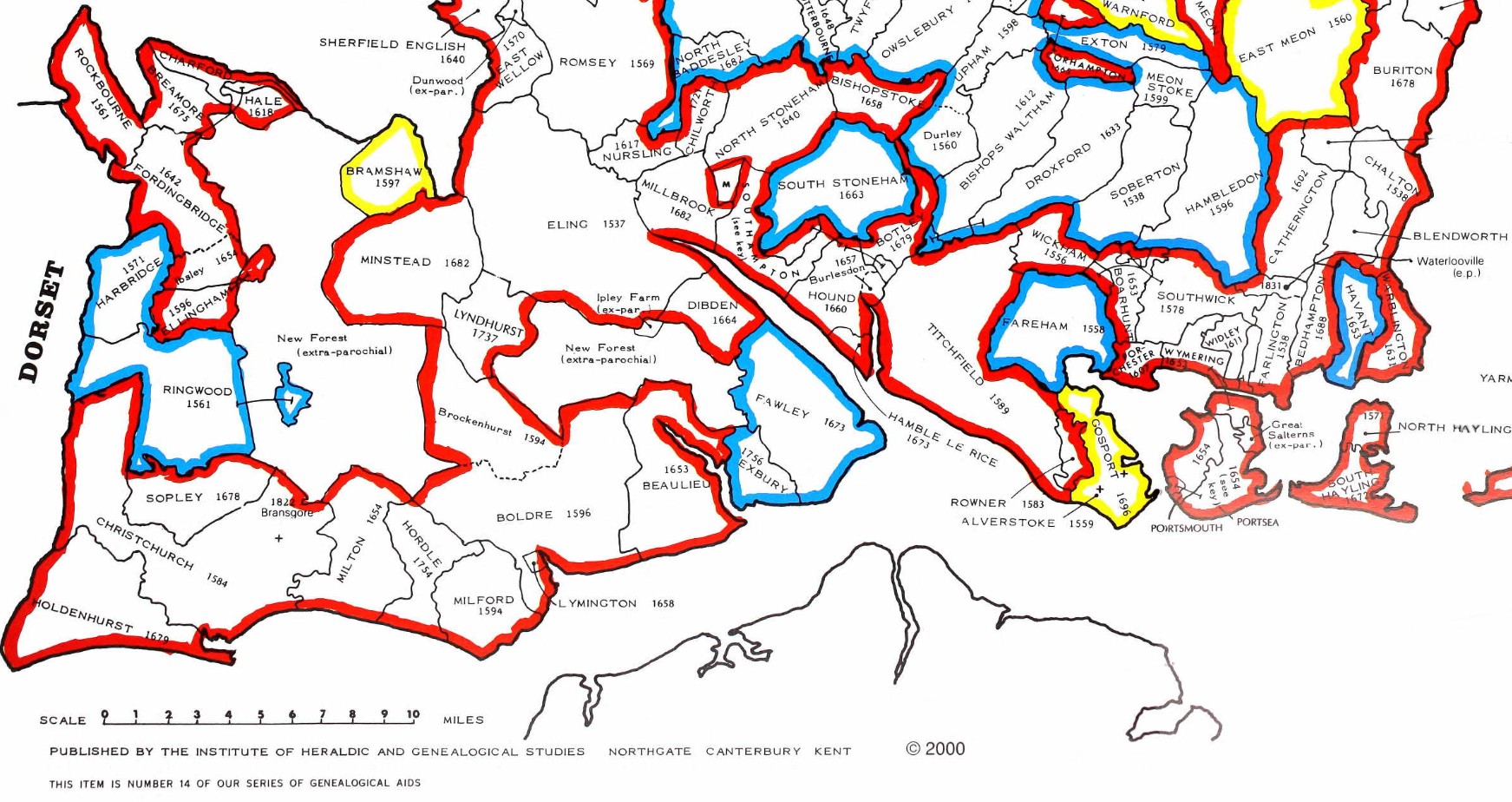

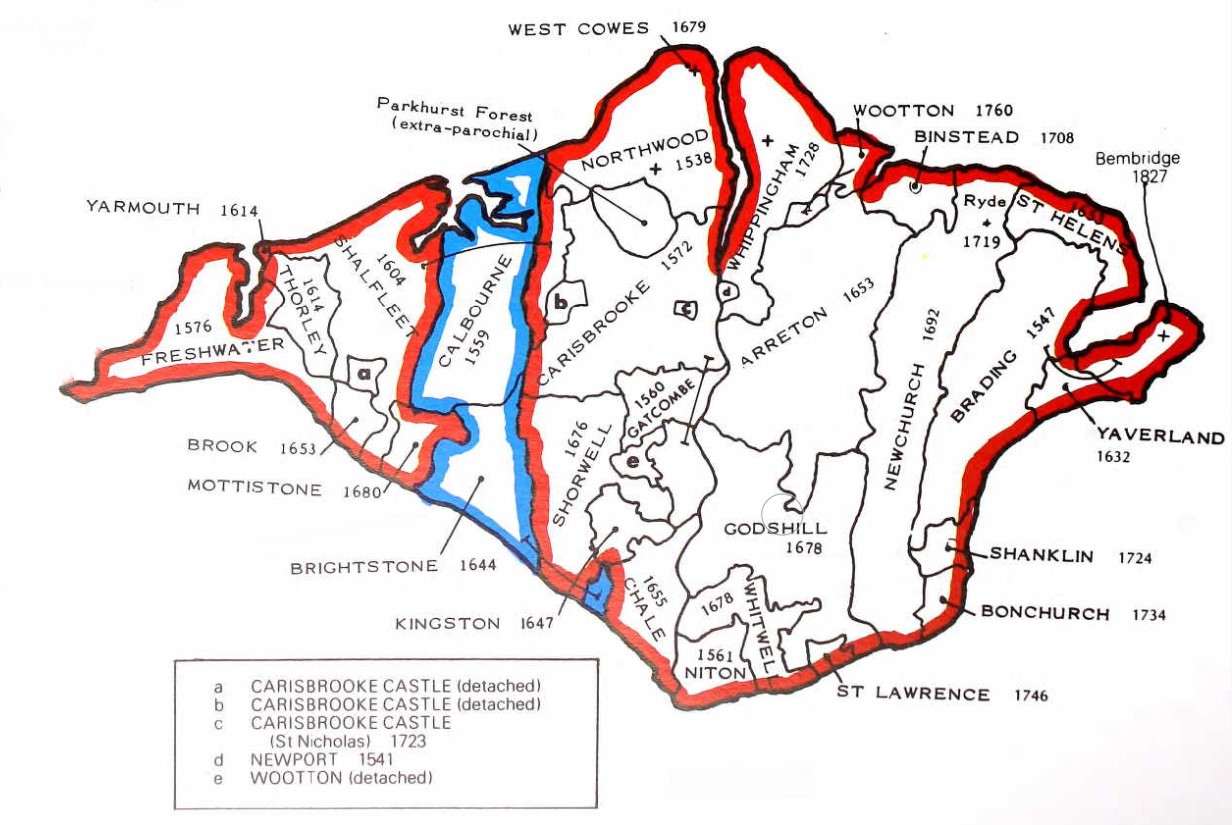

County map of Parishes - Hampshire

Extract from Great Britain, Atlas and Index of Parish Registers, from Ancestry

Same map but in more detail

The same map but zoomed in and split into four parts for ease of use.

There is a vertical overlap on each segment to try to avoid the difficulty of interpreting the information, reading at the joints.

At one time this was done with mouse rollover, but that no longer consistently works on all browsers, so back to static.

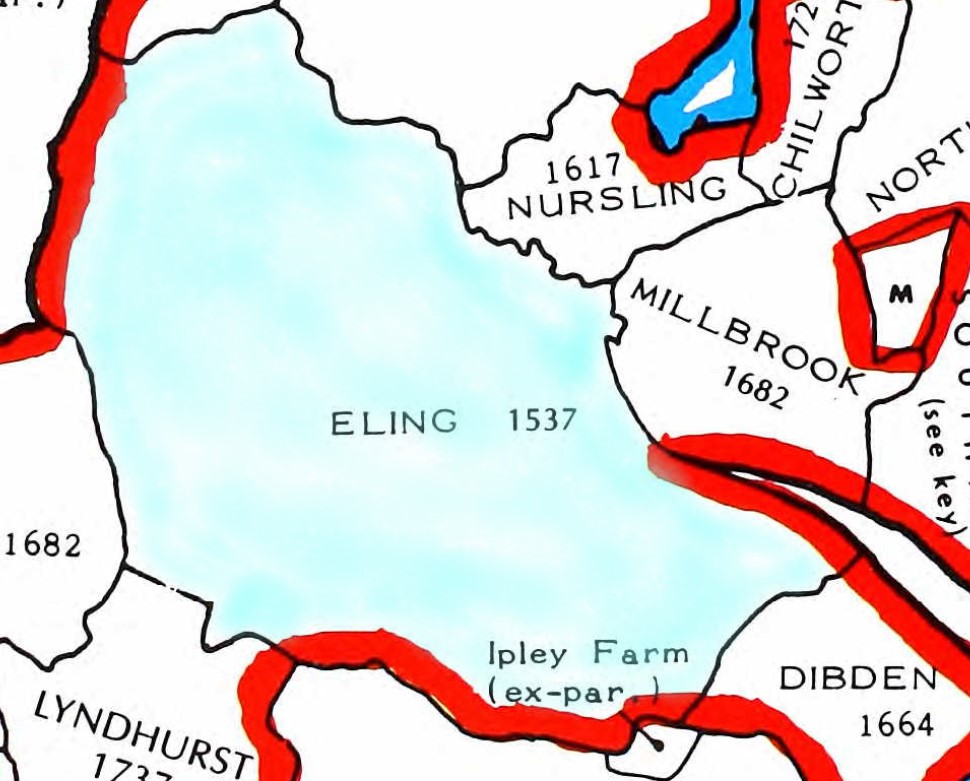

The County of Hampshire Parishes.

Zooming into the parish of Eling for this map, with a wash of light blue. Adjacent parishes to the North include Millbrook and Nursling. The dates indicate the early parish records.

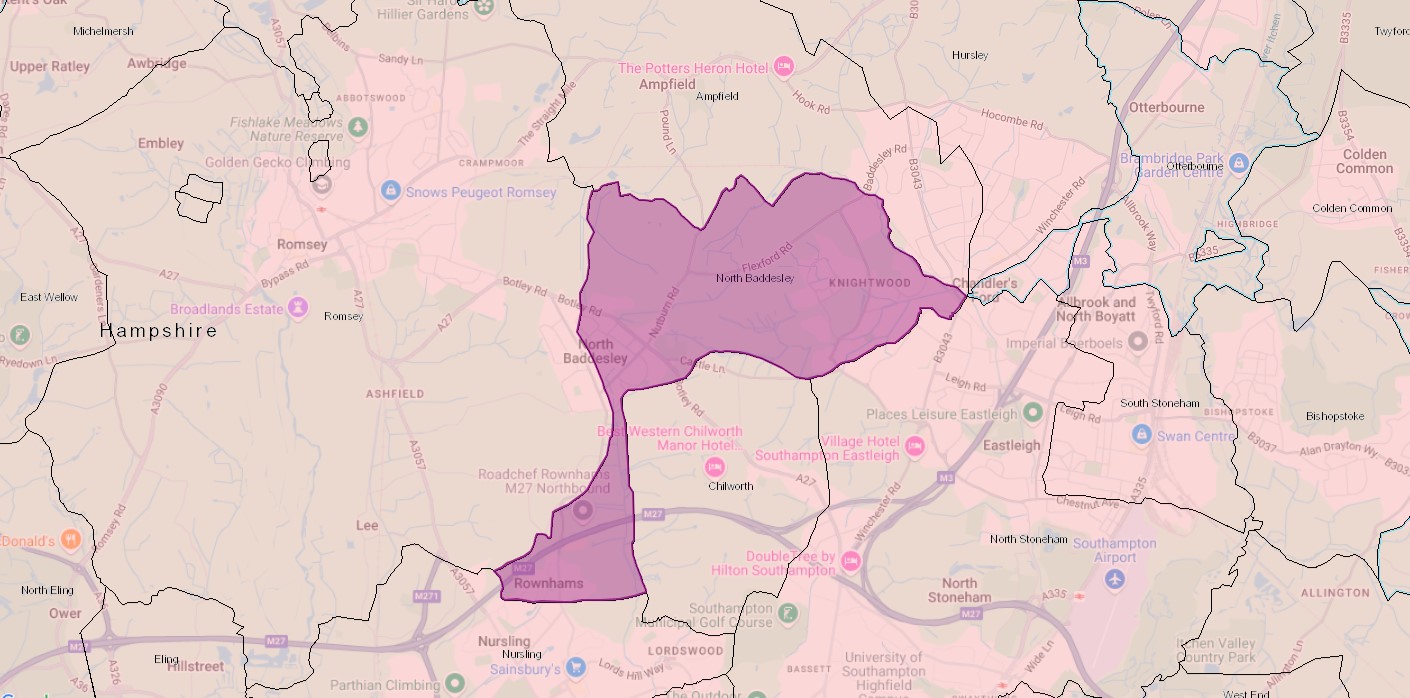

An extract of Family Search English Jurisdictions 1851. Search for Nursling, to get the map below.

A similar map but for the parish of North Baddesley, which includes Rownhams.

Rownhams was formerly a chapelry in the parishes of Nursling, Romsey and North Baddesley, on 1 October 1897 became a separate civil parish, on 1 April 1932 the parish was abolished to form "Nursling and Rownhams". In 1931 the parish had a population of 540.

St John’s Church in Rownhams was constructed in the 1850’s having been financed by Oliver Colt who lived in Rownhams House.

From Kelly's "Directory of Hampshire and the Isle of Wight (1911)"

ROWNHAMS is an ecclesiastical parish formed in 1856 from the parishes of Romsey Extra, Nursling and North Baddesley, and into a civil parish by Local Government Board Order No 36648, dated Oct 1st, 1897; it is 1½ miles north from Nursling station on the Southampton and Salisbury line of the London and South Western railway, 4 west-by-north-west from Southampton and 3½ south-east from Romsey, in the New Forest division of the county, hundred of Buddlesgate, union of Romsey, county court district of Romsey, rural deanery of Romsey and archdeaconry and diocese of Winchester, overlooking the valley of the Test, and bounded on the side by the road from Southampton to Romsey. The church of St. John the Evangelist is an edifice of stone in the Decorated style, consisting of chancel, nave, transepts, vestry, south porch and a tower with spire containing one bell and tubular chimes, hung in 1889 to the memory of the Rev. Robert Francis Wilson M.A. vicar here 1863-1888: in the chancel is a brass to William Oliver Colt, founder of this church, died April 9th. 1853, and Jane, his widow, by whom the work was completed about 1856, who died September 5th. 1875: the church was consecrated October 25th. 1856: all the windows are stained: the reredos is of alabaster, gilt and colored (sic): there are 220 sittings. The register dates from the year 1856. The living is a vicarage, net yearly value £190, with residence and 3 acres of glebe, in the gift of the Bishop of Winchester, and held since 1891 by the Rev. George Mead M.A. of St. John's College, Oxford. The vicarage house is of red brick in the Elizabethan still, and was erected by the late Mrs. Colt, of Rownhams Park. Rownhams House, the property and residence of Lord Abinger J.P. is a mansion of brick, situated in a park of 40 acres. The chief landowners are Wilfred W. Ashley esq. M.P., J.P. of Broadlands, Romsey, Mrs Vaudry-Barker-Mill, of Langley Manor, Tankerville Chamberlayne esq. of Cranbury Park, who is lord of the manor, and John E.A. Willis Fleming esq. of Chilworth Manor. The chief crops are barley, wheat and oats. The soil is clay, sand and gravel; subsoil, clay. The area is 1985 acres of land and 4 of water; rateable value , £3428; the population in 1901 was 498 in the civil and 481 in the ecclesiastical parish"

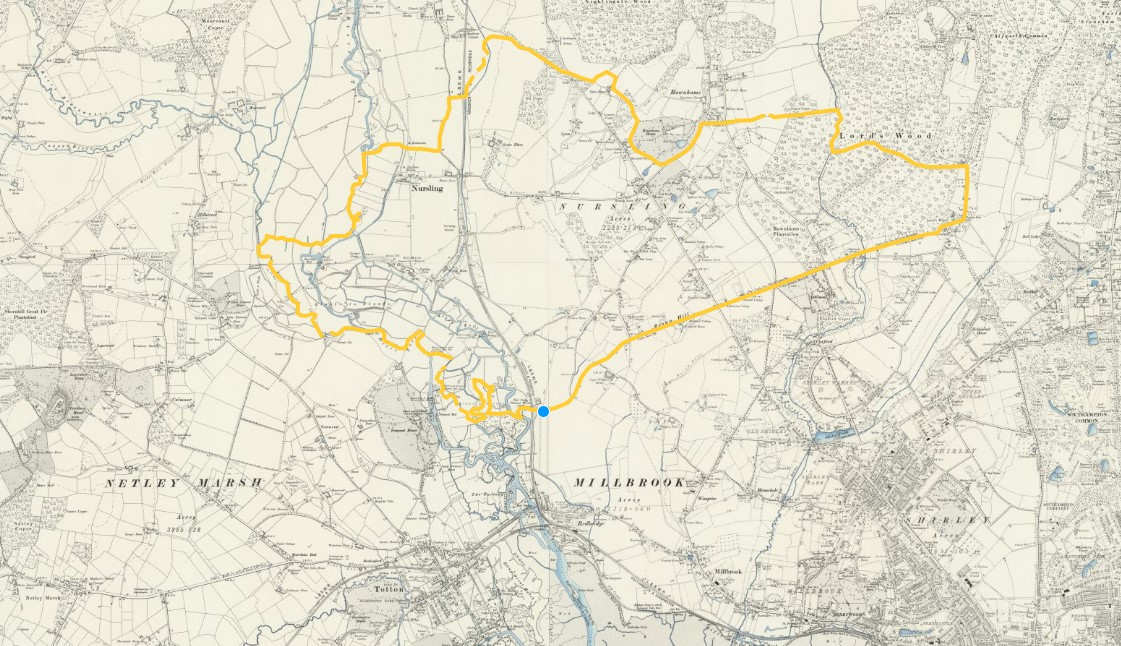

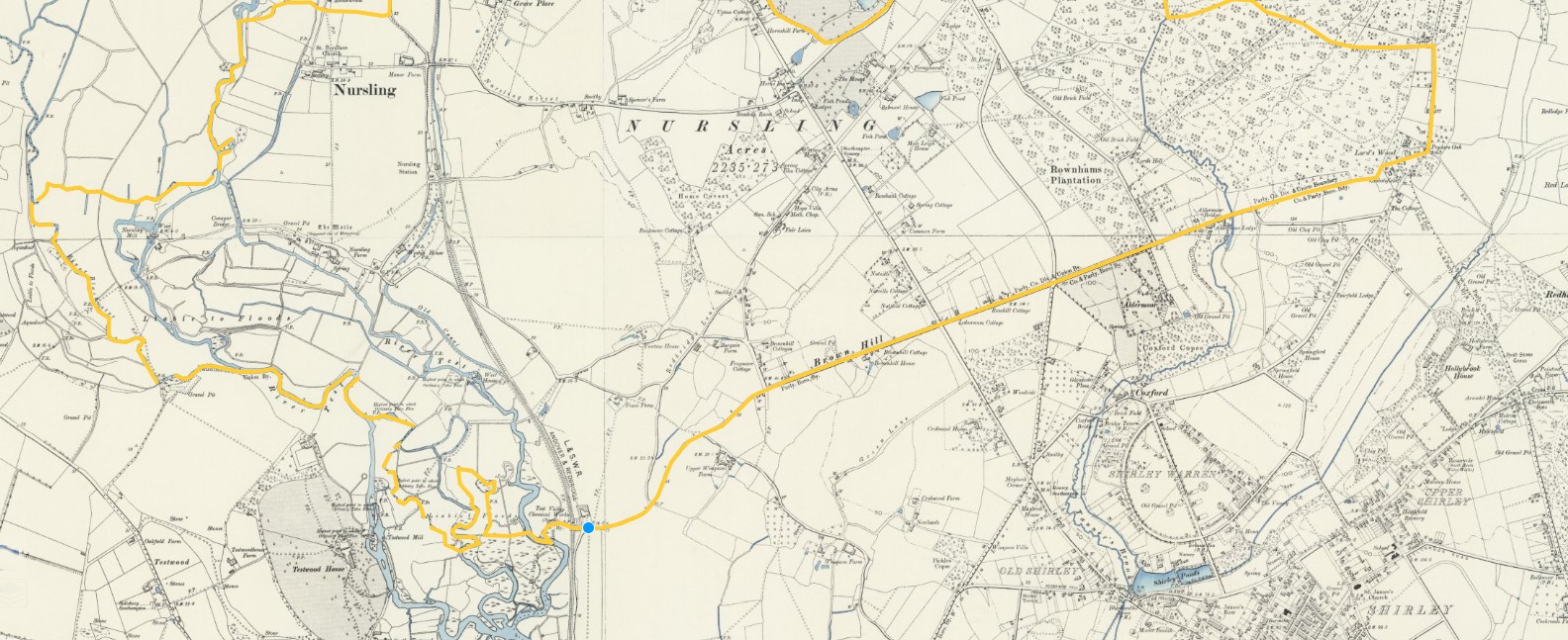

An Ordnance Survey, OS 6" Old Map from the National Library Of Scotland. The link will take you to a similar map, with the marker at St Boniface Church Nursling. The Map is made up from the following sheets;-

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LVII.SW

Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LVI.SE

Revised: 1895, Published: 1897

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LXV.NW

Revised: 1895 to 1896, Published: 1898

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Sheet LXIV.NE

Revised: 1895 to 1896, Published: 1897

Unfortunately, if you follow the link, the yellow line will not be there. I drew that onto the digital map using one of the tools. Zooming in a long way I followed the boundary markers, hoping they were the parish boundary.

You could also follow the doted line on the map at the link, for the detailed position. It may not be exactly the same boundary as shown on the English Jurisdictions 1851 map, above. Not only is there a time difference but the may be a difference between civil and ecclesiastical boundaries.

To get you a little closer, I have made copies of the above, zoomed in and split North and South.

I have not tried to align the two sheets. There are some vary torturous routes for the boundary, especially near the river.

All of the above maps of the Parish are before the separation and creation of a separate Rownhams Parish from lands of Nursling, Romsey, and North Baddesley Parishes, on 1 October 1897.

However, Rownhams House and the village of Rownhams do appear to be outside of the boundary shown. It is possible that the imminent boundary change was know and incorporated onto the maps as part of the revision.

Some of the dotted lines I have followed are Poor Law Union boundaries and others are Civil Parishes. Looking further at the key, I don't think the maps show ecclesiastical boundaries, so at least that is one potential variation resolved.

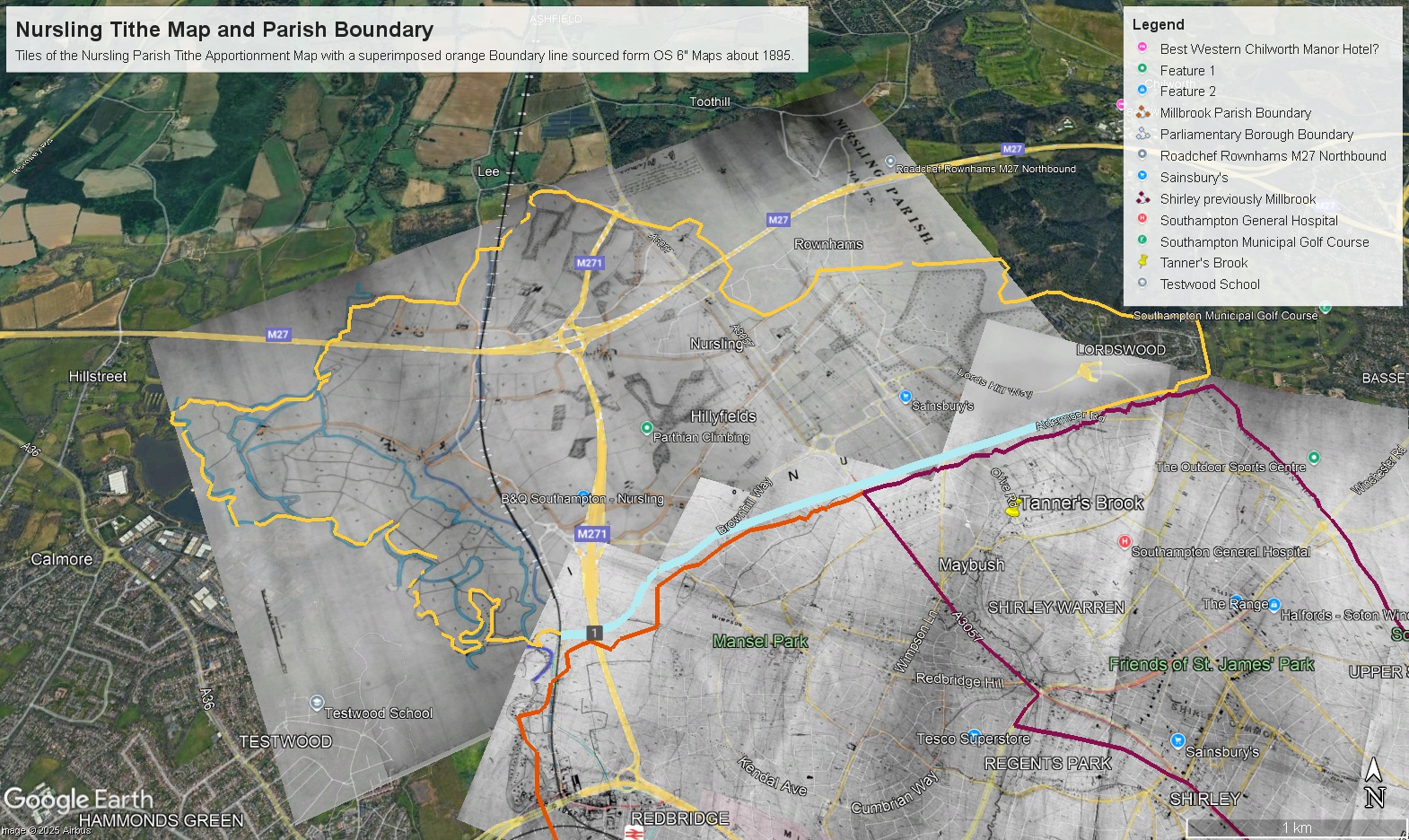

The above is a copy of a Google Earth image created by overlaying tiles of Nursling Parish Tithe Apportionment Map and the Boundary line created on the OS 6" maps above. Also shown is some of Millbrook Parish Tithe Apportionment Map. Although the lines and the edge of the Tithe Map do not align everywhere, there is a reasonable correlation. Apart for part of Lordswood, which appears to be missing. Although, on the original image it does go further into Lordswood, closer to the shape of the boundary. Something to rectify at a later date. The Tithe Apportionment is dated 19th Sept 1846. My conclusion therefore is that the orange line above is before the separation of part of the Parish for the creation of the Parish of Rownhams.

The above ESRI Church of England Parish map brings us up to date. Click on the map in the area of Nursling to bring up the boundary and information about the Parish. It does work here but it is easier to see if you first click on 'View larger map', which opens a new page. The statistics are fascinating. You can also click on one of the dots to bring up information about that. Click in different places to see different parts of the boundary, or adjacent parishes.

Before 1066

Your text...

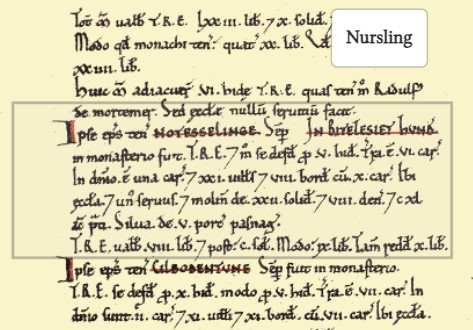

Domesday Book

Nursling in the Domesday Book of 1086

Nursling has also been called Nutshalling

Nursling was mentioned it the Domesday Book of 1086

Nursling was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Buddlesgate and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 30 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 40% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

Land of Bishop of Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin)

Households

Households: 21 villagers. 8 smallholders. 1 slave.

Land and resources

Ploughland: 6 ploughlands. 1 lord's plough teams. 10 men's plough teams.

Other resources: Meadow 140 acres. Woodland 5 swine render. 1 mill, value 1 pound 2 shillings and 7 pence. 1 church.

Valuation

Annual value to lord: 9 pounds in 1086; 5 pounds when acquired by the 1086 owner; 8 pounds in 1066.

Owners

Tenant-in-chief in 1086: Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin), bishop of.

Lord in 1086: Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin), bishop of.

Lord in 1066: Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin), bishop of.

Other information

Phillimore reference: Hampshire 3,2

Comparison to other nearby settlements.

By comparison, nearby settlements of Millbrook and Shirley. Which later became parishes, which subsequently merged, and then again separated.

Millbrook was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Mansbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 28 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 40% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

Land of Bishop of Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin)

Interestingly, for Millbrook, the lord in both 1066 and 1086 is stated as being 'villagers'

Shirley was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Mansbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 12 households in 1086.

Land of Ralph of Mortimer

Mortimer is a surname in my Family Tree. I wonder if there is a connection?

Nearby towns were Southampton, Romsey and Eling, 4.2 miles / 1hr 25 mins walk, 3.7 miles / 1hr 14 mins walk, and 3.6 miles / 1hr 13 mins walk respectively, according to Google Maps

Southampton was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Mansbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 185.5 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday, and is listed under 4 owners in Domesday Book.

Land of Bishop of Winchester (St Peter & St Swithin)

Romsey was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Somborne and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 127 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

Land of Romsey (St Mary & St Elfleda), abbey of

Eling was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Redbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 69 households in 1086, putting it in the largest 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday.

Land of King William

Between Nursling and Eling is Totton.

Totton was a settlement in Domesday Book, in the hundred of Redbridge and the county of Hampshire.

It had a recorded population of 20 households in 1086, and is listed under 2 owners in Domesday Book.

Land of Romsey (St Mary & St Elfleda), abbey of

and

Land of Aghmund, of Wellow

Before 1600

1600 to 1800

Tithe Apportionment and Map

Tithe Apportionment and Map

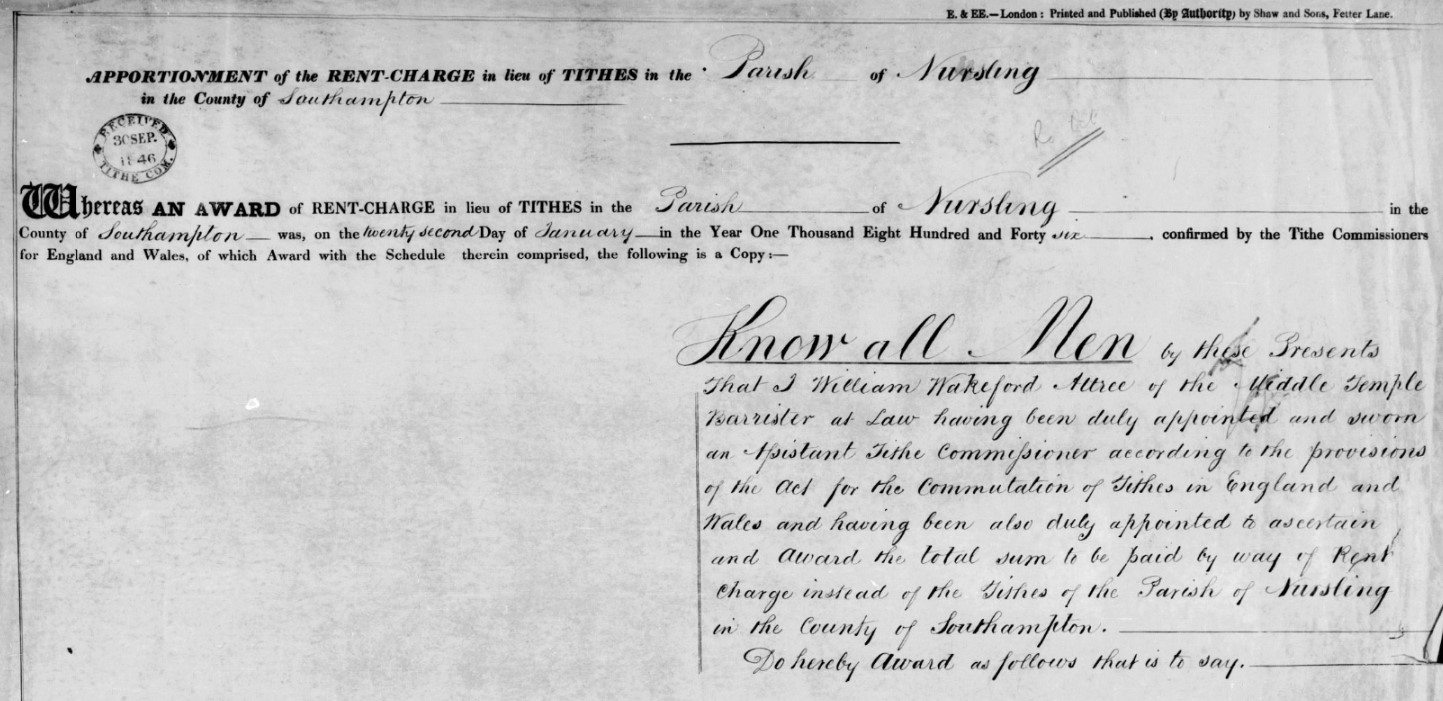

The Tithe Commutation Act 1836

An Act for the Commutation of Tithes in England and Wales. - 6 & 7 Will 4 c 71. Royal assent; 13 August 1836

Together with several amendments;

Act amended by Tithe Act 1839 (c. 62), Tithe Act 1842 (c. 54), Tithe Act 1860 (c. 93), Tithe Act 1878 (c. 42), Tithe Act 1891 (c. 8) and Tithe Act 1918 (c. 54)

The Tithe Act, 1936 (26 Geo. V and 1 Edw. VIII. C.43) abolished all tithe rent charges. Responsibility for tithe documents created under the tithe acts (1836, 1837, 1839, 1860, 1891) were placed under the charge of the Master of the Rolls, who has the authority to transfer them to an approved place of deposit. This responsibility is exercised by The National Archives: Historical Manuscripts Commission. The Master of the Rolls has issued Tithe (Copies of Instruments of apportionment) Rules 1960 (SI 1960/2440), as amended by the Tithe (Copies of Instruments of Apportionment) (Amendment) Rules 1963 (SI 1963/977)] concerning the care, custody, access to, and definition of tithe documents.

The start and end of Tithes.

Religion, of many faiths, the Established Church, the Pope, the Governments, and Kings of the time shaped the idea and practice of collecting tithes.

From a simple pious concept of the donation one tenth of your crop to the church, for charity, changed over time and created some very rich churches and some very poor people, and a degree of discontent.

Tithes lasted in England for over a thousand years, partly in goods and latterly as money.

All intertwined with a Norman, with Viking Blood, thinking he was the rightful successor to the English Throne, a Pope who wanted to bring Ireland into the European sphere, or should that read his sphere, and Henry VIII wanting to have a male heir to prolong the Tudor epoch. Little did he know Elizabeth I would be so good at being monarch. Power and politics, over centuries of time.

Splits in the Christian Church

There were three major schisms:

- 1) the one in the 5th century that split eastern Christendom in two;

- 2) the one the 11th century that divided the Latin church and the Byzantine church;

- and 3) the Reformation in the 16th century in which Protestantism arose and split from the Roman Catholic church.

2) On July 16, 1054, Patriarch of Constantinople Michael Cerularius was excommunicated, starting the “Great Schism” that created the two largest denominations in Christianity—the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox faiths.

3) The Reformation — more properly called the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation — was a 16th-century religious and political uprising against the authority of the Pope that led to was a schism in Western Christianity. It was initiated by Martin Luther with the publication of the “Ninety-five Theses” in 1517 and continued by Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and other Protestant Reformers. The Reformation triggered the bloody the Counter-Reformation, which sucked in much of Europe, and lasted until the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648. The Reformation led to the division of Western Christianity into different denominations such Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Anglican, Anabaptist and Unitarian. The Eastern Orthodox Christian church had split off in 1054.

The Reformation began as theological debate over real and perceived Church corruption. Early dissenters included John Wycliffe (1320-84) in England, and john Huss (burned as a heretic in 1415) in Bohemia. Martin Luther was from Germany. Other major players in the Reformation were Huldrych Zwingli of Zurich, John Calvin of Geneva and King Henry VIII of England

The Reformation was aided by the invigorated intellectual freedom of the Renaissance and spirit of nationalism in England, France, Germany and Bohemia. In the 16th century the church was corrupt and blemished by greedy clergy and decadent monks, extracting financial burdens from the laity to pay for their indulgences and ambitions. The General Councils of 15th century failed to reform he church. After the Reformation the power of the Catholic Church was greatly weakened

What is the relevance of these splits? The divisions within the Christian Church have in part contributed to the discontent leading to the Tithe Wars and the subsequent Tithe Commutation Act. The Act led to the creation of very useful set of documents for Family Historians, with information about people, places, and land usage.

Feudal system

A copy of some text from the ESRI Story Map of Whiteparish One Place Study

The feudal system and the Domesday Book

The feudal system was a way of organising society into different groups based on their roles. It had the king at the top with all of the control, and the peasants at the bottom doing all of the work.

How did the feudal system start?

The results created what's known as the Domesday Book. It actually described a wide range of ways in which people used the land, but historians suggested that it had a basic structure:

- King – owned all the land.

- Barons – the king gave some land to the barons in return for money and men for the army.

- Knights – the barons gave some of their land to the knights if they promised to fight when needed.

- Peasants – the knights gave a few strips of land to the peasants and the peasants had to share their produce with them. They were not allowed to leave and were not free men

In the Middle Ages, anyone who was higher up in this system than you was a 'lord' and of course the monarch had no one above them. What kept the system working was loyalty. Stay loyal and keep the land and wealth. Fail and your income was taken from you by your lord.

Centuries later the system was not hugely different and Tithes came into play.

Tithes were originally a tax which required one tenth of all agricultural produce to be paid annually to support the local church and clergy. After the Reformation much land passed from the Church to lay owners who inherited entitlement to receive tithes, along with the land.

The Tithe Acts of 1836 and 1936 abolished the old system, but two hundred years ago tithes were engraved upon the lives of the entire population: a source of income, luxury and avarice for the privileged; a tax at 2s

Before Tithes

Fifteenths and tenths, 1334

FIFTEENTHS AND TENTHS: QUOTAS OF 1334

'Fifteenths and tenths, 1334', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4, ed. Elizabeth Crittall (London, 1959), pp. 294-303. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol4/pp294-303 [accessed 24 June 2021].

By the last quarter of the 13th century Englishmen had become familiar with a system of tax assessment which took no account of such old-fashioned assessments of wealth as hides or knight's fees. This new system of assessment was based on a valuation of certain personal property, usually described by the vague word 'movables'. Of this value Parliament had granted the king a fraction: the fraction itself varied from grant to grant but in each grant a greater fraction was levied on cities, towns, and royal demesne than on other areas. Thus in 1332 the townsman found himself contributing a tenth of his assessed movables but the countryman only a fifteenth. In addition there were some categories of goods which the collectors were instructed to ignore, and as a result the statistics from the collections deal only with those Englishmen and women who were wealthy enough to fall under the scrutiny of the local assessors. It is rather like an iceberg the size of whose submerged depths is unknown. In addition there was probably evasion and under-assessment everywhere.

Frustfield Hundred 274s.

- Abbotstone (in Whiteparish);50s 0d

- Alderstone (in Whiteparish);13s 4d

- Cowesfield (in Whiteparish);100s 0d

- Landford; 66s 8d

- Whelpley (in Whiteparish); 44s 0d

Whiteparish does not appear as a separate settlement in 1334, assuming that the (in Whiteparish) is a later addition when the table was constructed from the original data.

Tithe background

Tithe background

From Wikipedia, extracts from articles about Tithes and Tithe Commutation

A tithe (/taɪð/; from Old English: teogoþa "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government.

Church collection of religious offerings and taxes - England and Wales

The right to receive tithes was granted to the English churches by King Ethelwulf in 855. The Saladin tithe was a royal tax, but assessed using ecclesiastical boundaries, in 1188. The legal validity of the tithe system was affirmed under the Statute of Westminster of 1285. The Dissolution of the Monasteries led to the transfer of many rights to tithe to secular landowners and the Crown – and tithes could be extinguished until 1577 under an Act of the 37th year of Henry VIII's reign. Adam Smith criticized the system in The Wealth of Nations (1776), arguing that a fixed rent would encourage peasants to work far more efficiently.

The system gradually ended with the Tithe Commutation Act 1836, whose long-lasting Tithe Commission replaced them with a commutation payment, land award and/or rentcharges to those paying the commutation payment and took the opportunity to map out (apportion) residual chancel repair liability where the rectory had been appropriated during the medieval period by a religious house or college. Its records give a snapshot of land ownership in most parishes, the Tithe Files, are a socio-economic history resource. The rolled-up payment of several years' tithe would be divided between the tithe-owners as at the date of their extinction.

This commutation reduced problems to the ultimate payers by effectively folding tithes in with rents however, it could cause transitional money supply problems by raising the transaction demand for money. Later the decline of large landowners led tenants to become freeholders and again have to pay directly; this also led to renewed objections of principle by non-Anglicans.[39] It also kept intact a system of chancel repair liability affecting the minority of parishes where the rectory had been lay-appropriated. The precise land affected in such places hinged on the content of documents such as the content of deeds of merger and apportionment maps.

Tithe redemption

Rent charges in lieu of abolished English tithes paid by landowners were converted by a public outlay of money under the Tithe Act 1936 into annuities paid to the state through the Tithe Redemption Commission. Such payments were transferred in 1960 to the Board of Inland Revenue, and those remaining were terminated by the Finance Act 1977.

The Tithe Act 1951 established the compulsory redemption of English tithes by landowners where the annual amounts payable were less than £1, so abolishing the bureaucracy and costs of collecting small sums of money.

Ireland

From the English Reformation in the 16th century, most Irish people chose to remain Roman Catholic and had by now to pay tithes valued at about 10 per cent of an area's agricultural produce, to maintain and fund the established state church, the Anglican Church of Ireland, to which only a small minority of the population converted. Irish Presbyterians and other minorities like the Quakers and Jews were in the same situation.

The collection of tithes was resisted in the period 1831–36, known as the Tithe War. Thereafter, tithes were reduced and added to rents with the passing of the Tithe Commutation Act in 1836. With the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland by the Irish Church Act 1869, tithes were abolished.

Tithe War

The Tithe War (Irish: Cogadh na nDeachúna) was a campaign of mainly nonviolent civil disobedience, punctuated by sporadic violent episodes, in Ireland between 1830 and 1836 in reaction to the enforcement of tithes on the Roman Catholic majority for the upkeep of the established state church, the Church of Ireland. Tithes were payable in cash or kind and payment was compulsory, irrespective of an individual's religious adherence.

Tithe payment was an obligation on those working the land to pay ten per cent of the value of certain types of agricultural produce for the upkeep of the clergy and maintenance of the assets of the church. After the Reformation in Ireland of the 16th century, the assets of the church were allocated by King Henry VIII to the new established church. The majority in Ireland who remained loyal to the old religion were then obliged to make tithe payments which were directed away from their own church to the reformed one. This increased the financial burden on subsistence farmers, many of whom were at the same time making voluntary contributions to the construction or purchase of new premises to provide Roman Catholic places of worship. The new established church was supported by only a minority of the population, seventy-five percent of whom continued to adhere to Roman Catholicism.

Emancipation for Roman Catholics was promised by Pitt during the campaign in favour of the Act of Union of 1801 which was approved by the Irish Parliament, thus abolishing itself and creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. However, King George III refused to keep Pitt's promises. It was not until 1829 that the Duke of Wellington's government promoted and parliament enacted the Roman Catholic Emancipation Act, in the teeth of defiant royal opposition from King George IV.

But the obligation to pay tithes to the Church of Ireland remained, causing much resentment. Roman Catholic clerical establishments in Ireland had refused government offers of tithe-sharing with the established church, fearing that British government regulation and control would come with acceptance of such money.

(British rule in Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169. Most of Ireland gained independence from Great Britain following the Anglo-Irish War as a Dominion called the Irish Free State in 1922, and became a fully independent republic following the passage of the Republic of Ireland Act in 1949. The papal bull Laudabiliter of Pope Adrian IV was issued in 1155. It granted the Angevin King Henry II of England the title Dominus Hibernae (Latin for "Lord of Ireland"). Laudabiliter authorised the king to invade Ireland, to bring the country into the European sphere. In return, Henry was required to remit a penny per hearth of the tax roll to the Pope. This was reconfirmed by Adrian's successor Pope Alexander III in 1172. When Pope Clement VII excommunicated the king of England, Henry VIII, in 1533, the constitutional position of the lordship in Ireland became uncertain. Henry had broken away from the Holy See and declared himself the head of the Church in England. He had petitioned Rome to procure an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Clement VII refused Henry's request and Henry subsequently refused to recognise the Roman Catholic Church's vestigial sovereignty over Ireland, and was excommunicated again in late 1538 by Pope Paul III. The Treason Act (Ireland) 1537 was passed to counteract this.

The Lordship of Ireland (Irish: Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between 1177 and 1542. The lordship was created following the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169–1171. It was a papal fief, granted to the Plantagenet kings of England by the Holy See, via Laudabiliter. As the lord of Ireland was also the king of England, he was represented locally by a governor, variously known as justiciar, lieutenant, or lord deputy.

The kings of England claimed lordship over the whole island, but in reality the king's rule only ever extended to parts of the island. The rest of the island—known as Gaelic Ireland—remained under the control of various Gaelic Irish kingdoms or chiefdoms, who were often at war with the Anglo-Normans.

The area under English rule and law grew and shrank over time, and reached its greatest extent in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. The lordship then went into decline, brought on by its invasion by Scotland in 1315–18, the Great Famine of 1315–17, and the Black Death of the 1340s. The fluid political situation and Norman feudal system allowed a great deal of autonomy for the Anglo-Norman lords in Ireland, who carved out earldoms for themselves and had almost as much authority as some of the native Gaelic kings. Some Anglo-Normans became Gaelicised and rebelled against the English administration. The English attempted to curb this by passing the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which forbade English settlers from taking up Irish law, language, custom and dress. The period ended with the creation of the Kingdom of Ireland in 1542.)

The Kingdom of Ireland (Classical Irish: an Ríoghacht Éireann; Modern Irish: an Ríocht Éireann, pronounced [ənˠ ˌɾˠiːxt̪ˠ ˈeːɾʲən̪ˠ]) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of the Kingdom of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from 1542 until 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then the monarchs of Great Britain. The kingdom was administered from Dublin Castle by a viceroy appointed by the English king — the Lord Deputy of Ireland. A Parliament of Ireland, composed of Anglo-Irish and native nobles, was created. From 1661-1801, the administration controlled an army. A Protestant state church — the Church of Ireland — was established. Although styled a kingdom, for most of its history it was, de facto, an English dependency.

The Protestant Ascendancy, meeting in their Parliament of Ireland, passed the Acts of Union 1800 which abolished both the parliament itself and the kingdom.[5] The act was also passed by the Parliament of Great Britain. On the first day of 1801, a new state — the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland — was established which united the parliaments of Ireland and of Great Britain into a single legislature — the Parliament of the United Kingdom.)

Scotland

In Scotland teinds were the tenths of certain produce of the land appropriated to the maintenance of the Church and clergy. At the Reformation most of the Church property was acquired by the Crown, nobles and landowners. In 1567 the Privy Council of Scotland provided that a third of the revenues of lands should be applied to paying the clergy of the reformed Church of Scotland. In 1925 the system was recast by statute and provision was made for the standardisation of stipends at a fixed value in money. The Court of Session acted as the Teind Court. Teinds were finally abolished by section 56 of the Abolition of Feudal Tenure etc. (Scotland) Act 2000.

Tithe Commutation History

Tithe Commutation History

The extract below is from the The National Library of Wales. The same applied to England.

What Were Tithes?

Tithes were payments made from early times for the support of the parish church and its clergy. Originally these payments were made in kind (crops, wool, milk, young stock, etc.) and usually represented a tenth (tithe) of the yearly production of cultivation or stock rearing.

There were 3 types of tithe:

- Predial tithes were the products of crop husbandry - such as grain, woodland, and vegetables

- Mixed tithes were the products of animal husbandry - such as calves, lambs, wool and milk.

- Personal tithes were the profits of man's labour - such as fishing or milling (and largely insignificant after 1549).

It is more usual to refer to tithes as ‘Great Tithes’ and ‘Small Tithes’. The great tithes, also known as the ’rectorial tithes’, were payable to the rector and generally comprised the predial tithes of corn, grain, hay and wood while the small tithes, also known as the ‘vicarial tithes’, were payable to the vicar and comprised all other tithes

The ownership of the tithe was a property right that could be bought and sold, leased or mortgaged, or assigned to others. This resulted in many of the rectorial tithes passing into lay hands - particularly after the dissolution of the monasteries. These tithes then became the personal property of the new owners, or lay impropriators. After the sale of the tithes forfeited to the Crown in the 1530s, about 22.8% of the net value of tithes in Wales were held by lay impropriatorsat the time of commutation in 1836. A vicar usually continued to have the spiritual care of the parish and to receive the vicarial tithes.

From early times money payments had begun to be substituted for payments in kind. Fixed sums (moduses) were substituted for some categories of production, particularly for livestock and perishable produce; while adjustable payments known as compositions, which were sometimes assessed annually, were increasingly being substituted in local arrangements in latter years.

The National Archives holds a similar text as a guide, however, it was archived in 2015. Below is an extract from the archived version, just in case it disappears. The current version is In The National Archives Research Guides

The history of tithes

Originally, tithes were payments in kind (crops, wool, milk etc.) comprising an agreed proportion of the yearly profits from farming, and made by parishioners for the support of their parish church and its clergy. In theory, tithes were payable on

(i) all things arising from the ground and subject to annual increase - grain, wood, vegetables etc.;

(ii) all things nourished by the ground - the young of cattle, sheep etc., and animal produce such as milk, eggs and wool; and

(iii) the produce of man's labour, particularly the profits from mills and fishing.

Such tithes were termed respectively predial, mixed and personal tithes. Tithes were also divided into great and small tithes; generally speaking, corn, grain, hay and wood were considered great tithes, and all other predial tithes together with all mixed and personal tithes were classed as small tithes. It was common, but by no means universal, for the great tithes to be payable to the rector and the small tithes to the vicar of the parish.

During the dissolution of the monasteries, much church land - and in many cases also the accompanying rectorial tithes - passed into lay ownership. These tithes became the personal property of the new owners or lay impropriators. Usually a vicar continued to have spiritual oversight of the parish and to receive its vicarial tithes.

From early times money payments began to be substituted for payments in kind, a tendency further stimulated by enclosures, particularly the parliamentary enclosures of the late18th century. Enclosures were often made in order to improve the land and its yield, and had they proceeded without some arrangements respecting tithes, the rectors, vicars and lay owners of the tithes would have received an automatically increased income, as indeed they did when cultivation was improved without preliminary enclosure. One object of the Enclosure Acts was to get rid of the obligation to pay tithes. This could be done in one of two ways: by the allotment of land in lieu of tithes, or by the substitution either of a fixed money payment or of one which varied with the price of corn (hence the name corn rents applied to payments in lieu of tithes). The limits of the land allotted, or of the land charged with a money payment, were generally shown on a map attached to the Enclosure Award.

Tithe commutation from 1836

Statutory enclosure was a purely local affair, prompted by local landowners. Although much of the country was covered, in 1836 tithes were still payable in the majority of parishes in England and Wales. Scotland and Ireland have a different history: the Acts cited in this research guide did not apply there. In 1836, the government decided to commute tithes (i.e. to substitute money payments for payments in kind) throughout the country. The Bill received Royal Assent on 13 August 1836; three Tithe Commissioners were appointed, and the process of commutation began. Although the Tithe Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will IV, c.71) is a long and complicated piece of legislation, the underlying principle was the simple one of substituting for the payment of tithes in kind corn rents of the same sort as were already payable in many parishes under the authority of a local Enclosure Act. These new corn rents, known as tithe rentcharges, were not subject to local variation, but varied according to the price of corn calculated on a septennial average for the whole country. Existing corn rents were left unaffected: they continued to be paid according to the varied provisions of the local Acts which created them.

The first task of the Commissioners was to discover to what extent commutation had already taken place. Enquiries were directed to every parish or township listed in the census returns.

The initial process in the commutation of tithes in a parish was an agreement between the tithe-owners and landowners or, in default of agreement, an award by the Tithe Commissioners. Generally the next stage was the apportionment of payments, and the substance of the preceding agreement or award was then recited in the preamble of the instrument of apportionment.

Tithe maps

The Tithe Maps are by no means as uniform as the apportionments (see Section 6), varying greatly in scale, accuracy and size. At the outset, the Tithe Commissioners had attempted to secure a uniform and high standard. However in most cases there was no suitable map already in existence, and while there were many skilled land surveyors available, the expense of any new survey had to be met by the landowners. Insistence upon a fixed standard would have retarded the progress of commutation, so concessions therefore had to be made. When the 1836 Act was amended in the following year, a provision was inserted to the effect that, whilst every tithe map should be signed by the Commissioners, a map or plan should not be deemed evidence of the quantity of the land, or treated as accurate, unless it was sealed as well as signed by the Commissioners (Tithe Act 1837, s.1). Approximately 1,900 only of the tithe maps - about one-sixth of the whole - were sealed by the Tithe Commissioners, and it is these alone - called first-class maps - which can be accepted as accurate. The unsealed (or second-class) maps constitute a very mixed collection - indeed, some are little more than topographical sketches.

In many cases, discrepancies between apportionment and map subsequently created difficulties in the administration of payments and redemptions. At the time of the survey, when all the landowners concerned were well acquainted with the ground, the exact area of a piece of land or its precise delineation on a map might have appeared of little significance. The matter assumed more importance as time went on, particularly when readily-identifiable tithe areas vanished as a result of later developments. It is unnecessary to discuss in detail the problems of interpreting a tithe map; but it is well to bear in mind that reliance cannot be placed upon the area of individual tithe areas stated in an apportionment or computed from the tithe map, unless the map is sealed.

The numbers of the tithe areas on the map correspond to those in the schedules to the apportionment. These numbers are not consecutive.

Back to the The National Library of Wales.

The tithe maps

The accuracy of the maps depended on the skill of the local surveyors employed on the task. More than 200 different surveyors worked in Wales.

The first specification (British Parliamentary Papers, Session 1837, Vol. XLI 405) for the mapping proved to be over-ambitious. This was drawn up by one of the Assistant Commissioners, Lieutenant R K Dawson of the Ordnance Survey, and was intended to be at the scale of 3 chains to the inch (1:2,376) with a standardised set of symbols.

Unfortunately, this was not adopted, because the landowners had to pay the costs of the survey and many were unwilling, especially if they already had estate plans that could do the job.

Amending legislation had to be passed in 1837 permitting the presentation of less accurate maps, often on a smaller scale. Many of these maps were compiled from existing estate maps and involved very little new surveying.

Those maps that met the standard were calledfirst-class plans and received a seal from the Tithe Commissioners. The Tithe Commissioners refused their seal to inferior plans.

In Wales only 50 of 1,091 were sealed as first-class maps, mostly for Districts in Monmouthshire or Breconshire. The remainder were simply certified as being the documents on which the tithe rent-charge apportionment was based.

These second-class maps vary in scale and quality; there are some at the prescribed scale of 3 chains to the inch which for some reason were not sealed as first-class maps; while others are little more than topographical sketches and of no value for information about property boundaries, e.g. Llangeitho, Cardiganshire (1:7,920) and Nantglyn, Denbighshire (1:21,120). Some maps were simply enlargements of the Ordnance Survey One-inch maps.

How I make use of Tithe Apportionment and Maps

How I make use of Tithe Apportionment and Maps

The first part of this is to record the process of how I create information out of the historic data, followed by what I subsequently do with that information.

The end goal is to create sharable information for Family Historians and for myself. My choice of Parishes is reflective of my own Family Tree at the location of key ancestors in the period that the Surveys and Agreements were undertaken, about the 1840's

Introduction

Introduction

Your text...

Creating the Dataset

Creating the Dataset

The original schedule is hand written on paper. Scans of those paper pages have been made. Fortunately, most of the handwriting is a lot easier to read that mine.

The images from those scans are available for the Hampshire Record Office and The Genealogist. The former also holds the original documents which can also be viewed by arrangement.

Analog images are very interesting but the data needs to be digitised to allow it to be readily accessed and interrogated.

Transcription from the scans is not very difficult but is time consuming.

Key to creating the dataset is to have somewhere to put it.

Summary

Your text...

Schedule

Your text...

Additional information

Your text...

Output

Your text...

Geolocation

Geolocation

Matching the Tithe Map to current Mapping

As stated above, It is unnecessary to discuss in detail the problems of interpreting a tithe map; but it is well to bear in mind that reliance cannot be placed upon the area of individual tithe areas stated in an apportionment or computed from the tithe map, unless the map is sealed.

I therefore resort to comparing the Tithe Maps to the Ordnance Survey 25" maps held by The National Library of Scotland and prefer the Georeferenced Mapping.

It is not that easy to see the correlation with the OS Map with it's Northerly orientation compared to a Tithe Map which is normally arranged to best fit the paper.

Sometimes I can rotate a digital copy of the Tithe Map 90o or more, to approximate the Compass Rose northerly direction. It is then more discernible as to whether it is the same location as indicated on the 25" OS Maps as being the same as the Tithe Map.

Unfortunately Tithe Maps are frequently without place name annotations. So it is generally down to shapes to enable identification of the places by comparison to both old and current maps.

The shapes of the rivers, roads, and fields as well as the plot numbers confirm that it is the same hand drawn map. Fields are amazingly often the same shape now and then.

Another point of help can sometimes be the Apportionment Schedule, if the plots have named places which can be identified and found on the comparison map.